Canceling Unemployment Expansion Deepens America’s Commitment to Racist Labor Practices [Op-Ed]

As the country continues to prematurely reopen, measures of the economy reveal that we’re dealing with a worse recession than the one that followed the financial crisis of 2008. More than 40 million people have filed for unemployment nationwide, and estimates put the real unemployment rate at more than 20 percent.

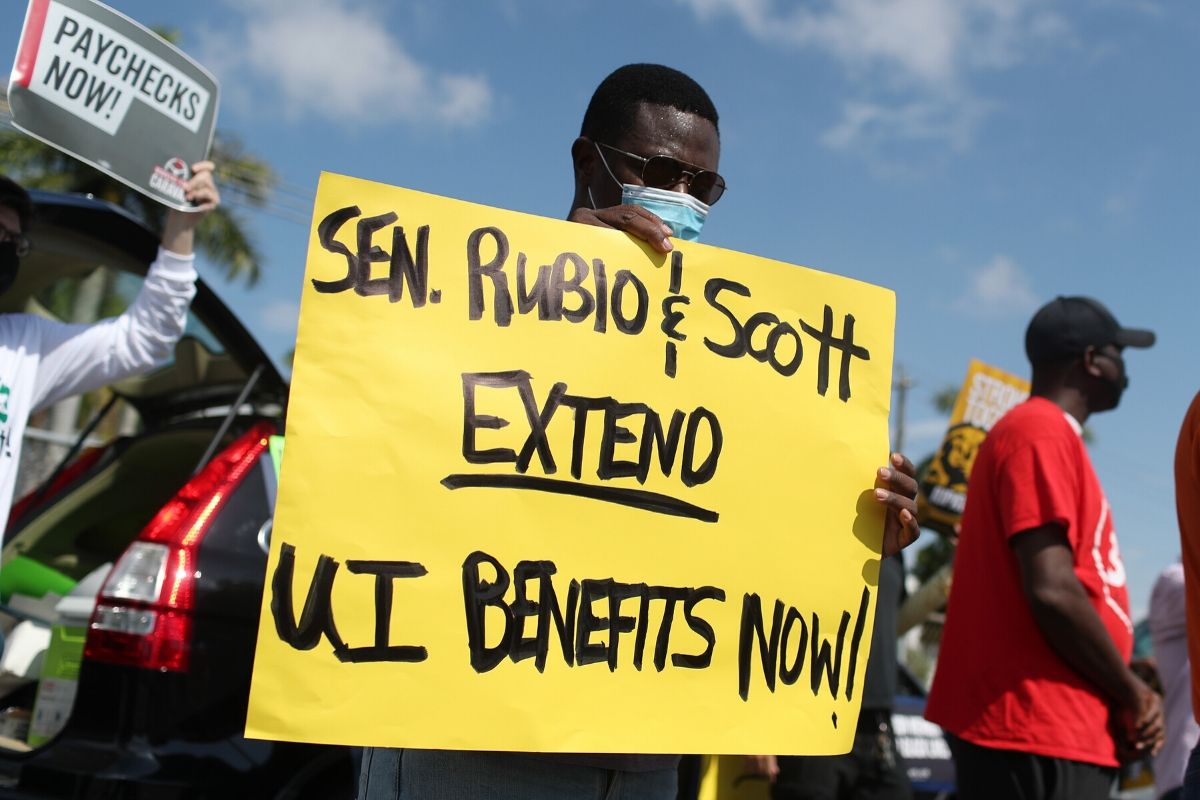

While the CARES Act did not go far enough to stop this economic tailspin, it did include provisions that are helping families survive, including the expansion of unemployment insurance by an additional $600 per week. This boost means that individuals who were forced to stay home when it became unsafe to work can access food, healthcare, and other necessary expenses. The expanded unemployment insurance was essential for people—particularly Black and brown folks—and businesses, and it must continue in order to protect people and keep money flowing through the economy.

Congress will soon choose whether to extend or cancel the unemployment insurance expansion. Initial reports show an argument taking hold among conservatives that the expansion disincentivizes people to return to work. These conservatives argue that many people make more money on unemployment than they did at their jobs, so they have no reason to go back. This heavily coded argument isn’t new; in fact, it’s rooted in a long history of racist labor policy in the United States. The good news is that the current moment provides a chance to counter it.

Unemployment insurance is one of the most frequently used programs that came out of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. To pass it, Roosevelt and other policy architects had to get racist Southern Democrats on board. Among the most important things for these Democrats was maintaining the social order of Jim Crow. At that time, both domestic work and farming were industries that were heavily populated by Black workers, especially in the South.

To get buy-in from the South, reformists agreed to exclude those workers from this crucial piece of New Deal legislation. In fact, most farmworkers did not become eligible for unemployment insurance until the CARES Act, and many domestic workers who are classified as self-employed were still left out of provisions this time around. That means that during all of the periods of economic downturn since the 1930s, domestic and farmworkers—who are still primarily Black and Latinx—were not eligible for the same safety nets as their white counterparts.

Fast forward to the 1990s, when politicians on the right employed dog whistles to debate welfare reform. Even though it has always been true that there are more white than Black people using welfare programs, the image of the “welfare queen” plays on America’s racism and demonization of people of color who dared accept help from the same government that institutionalized racism. This demonization persists today—this fictional woman who refuses to work and thrives on handouts from the government is frequently evoked in discussions about government spending on social programs. It’s an American pastime to characterize Black workers as lazy, and to label any attempt to help us as encouraging our inherent laziness.

It’s true that the CARES Act helped many workers make more than they did at their jobs; some food service workers, janitorial workers, medical assistants, sales and retail workers, transportation workers, construction workers and even teachers are making above their normal earnings. A study from the University of Chicago finds that 68 percent of unemployed workers who can receive benefits are eligible for payments that are greater than their lost earnings.

How should we respond to this fact? Well, Republicans would like to respond by pushing people to risk their lives and languish on the verge of literal starvation in order to return to work during the deadliest pandemic in generations.

If you’re thinking that there has to be a better way to handle this, you’re right. All of the professions listed above—and many more impacted by the economic fallout fueled by COVID-19—have long been the target of attacks on workers organizing in order to keep wages down. The expansion of benefits means that workers in these fields are finally seeing a wage that comes close to—but still doesn't equal—a truly livable wage.

In addition to calling for the cancellation of rent during the pandemic, workers and advocates are clamoring for unemployment expansion to be extended beyond the fast-approaching end, but we must go further than that. The additional money being allocated to folks on unemployment should be a lesson on why workers who have been surviving on poverty wages for decades deserve better, and that paying people, fairly and en masse, is well within our reach.

Now is the time to increase worker power, pay, and workplace protections, so that people are never again forced to risk their lives just to barely scrape by on their bills.

Most everyone in the world would like life to return to some level of normalcy. Let’s work together to make sure our new normal provides Black and brown workers the resources and protection we’ve deserved all along.

Maurice BP-Weeks is the Co-Executive Director of Action Center on Race and the Economy. He works with community organizations and labor unions on campaigns to go on offense against Wall Street to beat back their destruction of communities of color.