Supreme Court Case Asks if Prosecutors Engineered an All-White Jury

In late May the Supreme Court said it would hear the case of Timothy Foster, a black 18-year-old with intellectual disabilities who was sentenced to death for the 1986 murder of a white, 79-year-old retired schoolteacher, Queen White. The jury that convicted Foster of the Rome, Georgia, murder was all white. Now, nearly 30 years later, attorneys from the Southern Center for Human Rights have court documents that they say prove that prosecutors systematically eliminated every black potential juror in the Foster case.

When it comes to race, the rules for jury selection are best outlined by the Supreme Court’s 1986 decision in Batson v. Kentucky, which stipulates that both sides can eliminate potential jurors without cause. But there’s a catch: They can’t do so based on race. But in practice all-white juries are allowed even when the defendant is non-white. That’s because Batson allows prosecutors to describe their approach as “race-neutral" and claim that they're eliminating each non-white potential juror for a reason besides their race. So long as the trial judge goes along with it, all-white juries are free to determine the guilt or innocence of defendants of color.

Because courts tend to take the word of prosecutors who claim they're "race-neutral" it's difficult to prove that they are discriminating against non-white jurors. But the prosecutors in the original Foster case took unusually revealing notes about the race of potential jurors. Documents provided to Colorlines by the Southern Center for Human Rights indicate that of the 178 people in the original jury pool only 13 were black. In the end, 42 people were determined to be qualified to serve on the jury—and only four of them were black. On four separate copies of the prosecutors’ list of potential jurors, each black person's name is highlighted in green.

{{image:2}}

But Foster's prosecutors didn't just mark all of the potential black jurors with green highlighter. They also referred to some of them as B#1, B#2 and B#3:

{{image:3}}

Prosecutors also took revealing notes about white potential jurors. In case documents one potential juror is identified as a “skinny young [white female],” and at least two others are described as “attractive”:

{{image:4}}

Foster’s prosecutors also asked potential jurors direct questions about race. They asked people what kinds of neighborhoods they lived in and whether they could be impartial in a trial of a black defendant accused of murdering a white woman.

{{image:5}}

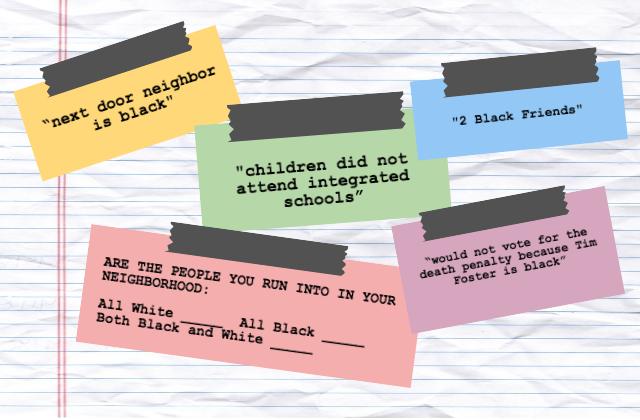

Prosecutors documented whether white potential jurors knew or interacted with black people. In several notes about race and segregation, they pointed out that a white potential juror's “next door neighbor is black,”and that their “children did not attend integrated schools.” Another white potential juror, it was noted, had “2 Black Friends”:

{{image:6}}

In one document prosecutors note that a potential juror “would not vote for the death penalty because Tim Foster is black”:

{{image:7}}

Foster appealed his conviction claiming that his capital trial with an all-white jury was unfair, but Georgia’s Supreme Court sided with prosecutors, who denied using race to exclude jurors.

Prosecutors nationwide will likely be watching how the Foster case fares in the U.S. Supreme Court. If the high court rules in Foster’s favor, it will send a message to that a claim of "race-neutrality" isn't enough to prove that prosecutors aren't using race in jury selection. If the SCOTUS rules in Georgia’s favor, however, it would essentially sanction discriminatory jury selection, even in matters of life and death.