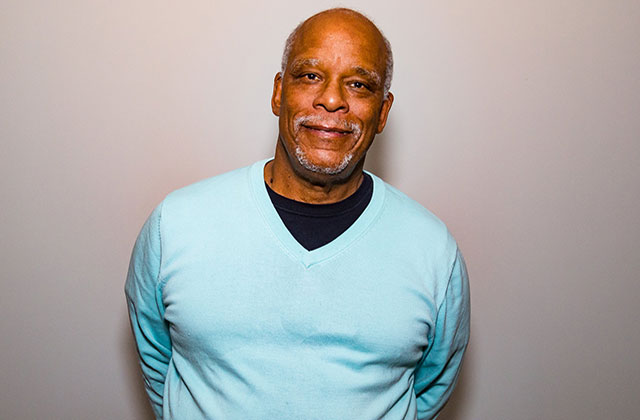

Filmmaker Stanley Nelson to Hollywood: Let Black Folks Tell 2020’s Story

As the film industry struggles to get back to business in the midst of COVID-19’s social distancing rules, famed documentarian Stanley Nelson (“Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool,” “The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution”) wanted to set the scene first with his recent Los Angeles Times editorial titled “Why we need Black filmmakers to tell the story of 2020.”

"For over 30 years, I’ve been making documentary films on the African American experience, particularly misrepresented or forgotten histories, including about Marcus Garvey, the murder of Emmett Till, the Freedom Riders, Freedom Summer and the Black Panther Party,” Nelson wrote. “Spending time with the folks who lived this history made me keenly aware that those who have the power to tell the story create the meaning of that story.”

But now, he continued, “the story shouting out at us today is one of national reckoning. The brutal killing of George Floyd may have ignited the protests. But it was the COVID-19 pandemic that re-arranged the firewood.”

Much like the editors whom Nelson cites of the nation’s first Black-owned newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, said in 1827 about not allowing others to tell their stories, the filmmaker is demanding the same for cinema. “No American institution has perpetuated our racial hierarchy, racist attitudes, and myths that twist the truth of our history more than film and television,” Nelson wrote, noting the canceling of “Cops” and the contextual disclaimer for “Gone with the Wind.” But that’s not enough, Nelson argues. What’s needed is systemic change.

For more must-read excerpts from the editorial, see below:

On modern cultural powder-kegs:

The pandemic doesn’t show how we were all in this together. Rather, it shows that everything is connected: how centuries of forced labor, Black Codes, Jim Crow and segregation, along with housing, economic and education inequality, have created a form of American apartheid that is playing out in who lives and who dies from the coronavirus.

The cultural uprising now underway is the result of decades of Black people telling their stories. But we’re not there yet. The stories documentarians and journalists capture today—and that will emerge in the weeks and months ahead as definitive narratives—will not only shape how we remember this extraordinary period but also how future generations come to understand it. It is therefore critical that African Americans and other people of color who are at the center of this revolution tell the stories.

The problem with fundraising:

It took me six years to raise the funds for a film about the Black press. And each new film is a challenge to finance. Just this year, my film company started seeking funding for a film on the 1921 Tulsa race massacre, now famous because of President Trump’s visit to Tulsa, originally planned on Juneteenth. Until recent events, we were told repeatedly by funding and production executives that they had never heard of it, that it was too unknown to have appeal. As everyone now recognizes, the Tulsa massacre is foundational to the African American experience in the 20th century.

In the documentary field, as in many others, decision-making is shrouded in secrecy, access is governed by close personal relationships and principal gatekeepers with the power to make or break careers are nearly all white. For many of the more than 100 filmmakers we’ve supported at Firelight Media Documentary Lab over the last decade, even winning the top awards in our field is not enough to break through.

Let the people (of color) tell their own stories:

It’s time that film distribution companies, financiers and film festivals made a commitment to transformation of their leadership. White directors and producers who want to tell stories about people of color should instead help a filmmaker of color to tell that story. Production companies and sales agents who leverage long-standing industry relationships should examine how their practices marginalize filmmakers and audiences of color.

Most importantly, the industry must move resources to filmmakers of color to tell the stories we all need to hear. Stories by and about Black, Indigenous and people of color are woefully lacking financial support, in part because the businesses that market, distribute and broadcast films in the United States have shown scant interest in reaching this demographic and little if any confidence that larger audiences would watch their stories.

To read the complete editorial, check out the LA Times here.