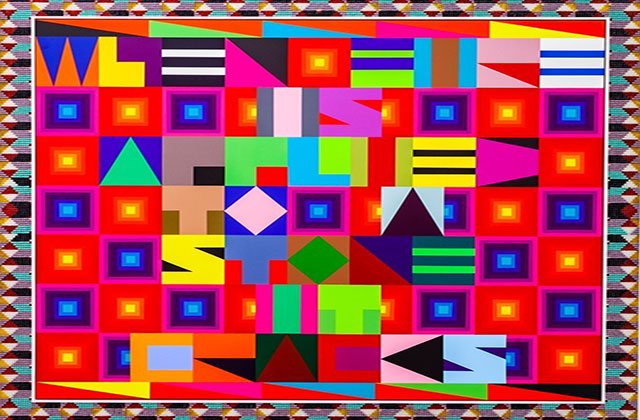

When visual artist and MacArthur Fellow Jeffrey Gibson, who is of Choctaw and Cherokee descent, creates art, he envisions a new dialogue between his work and previous representations of Native Americans. Now at the Brooklyn Museum in New York City, through January 10, 2021, Gibson is showcasing the multimedia exhibition “When Fire Is Applied to a Stone It Cracks,” to question “long-held institutional categorizations and representations of Indigenous peoples and Native American art,” according to the museum’s website.

Throughout the exhibition, Gibson tackles the issue of false representation by juxtaposing his recent work alongside that of selected objects from the museum’s collection in three parts. The entrance gallery shows representations of Native Americans by non-Native artists, including Charles Cary Rumsey’s “The Dying Indian” (1900s); the main gallery features Native artists; and the third uses the museum’s archives to illustrate the formation of its Native American collection from 1903 to 1929, by curator of ethnology Stewart Culin.

Regarding images like “The Dying Indian,” Gibson told AMNY in a March 8 article that they “have always saddened and perplexed me because I have never understood why some people celebrate these sculptures while I have found them offensive since I was a child. These sculptures present images of Native people that are idealized in the mind of the maker either for the objectification of their beauty or their demise.”

Equally offensive to Gibson was Culin’s curation, which AMNY described as having a racist slant that the artist, and collaborator and Bard College historian Christian Crouch sought to address. “The material in this room rejects the romanticized idea of the West—a false, vanishing frontier—or the reductive theatricality of the Wild West show,” AMNY reported Gibson and Crouch wrote in the third gallery. “We aimed to mute Culin’s voice in order to return the focus to Native people represented in the Archives and reports, who went about their daily lives and projected distinct representations of themselves.”

Learn more about the exhibition here.