When The Atlantic writer Adam Serwer published “The Cruelty is the Point,” the title phrase resonated with many critics of the Trump administration. It encapsulated many of administration’s brutish policies (from the Muslim ban to child separation at the Mexican border, among many others) and the mean-spiritedness of President Trump himself.

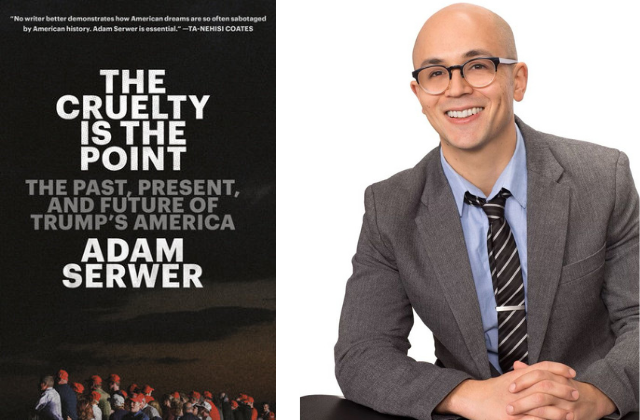

Though the phrase was emblematic of the last presidency, Trump’s moral ineptitude seemed so self-evident that saying he was cruel felt like saying water is wet. But in reading Serwer’s new book and collection of his writings during the 45th administration, “The Cruelty is the Point: The Past, Present, and Future of Trump’s America,” the weight of the phrase becomes clearer.

In his essays, Serwer serves both as witness to Trump’s time in office, while also connecting the historical politics and ideologies that produced him. He discusses a number of issues and topics, including the roots of American nationalism, the mixed responses to the Black Lives Matter movement, anti-semitism, police unions and the retrenchment that always follows period of progress. Ultimately, Serwer wants us to recognize though President Trump “may have appeared to be the driver of forces tearing the country apart, he was more a consequence of them, of our failure as a nation to live up to our founding promises. The cruelty was the point, but it always was a part of us.”

In this interview with Colorlines, Serwer explored how he came up with the “cruelty is the point” phrase, the timing of his book release during the moral panic over critical race theory and how he thinks historians will handle Trump’s legacy.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Your phrase “The cruelty is the point” has resonated with those critical of the Trump administration. Was there any particular event or action by the former president and his administration that sparked this idea?

I think the phrase merely described a phenomenon we had all observed, but the proximate inspiration for it was when the president mocked Christine Blasey Ford. What struck me about the hearing was that she had said the thing she remembered the most was the laughter of Kavanaugh and his friend, and Trump seemed to zero in on that and he was intent on mocking her for coming forward and making the audience laugh at her. He viewed her words as an emotional weakness he could exploit. For that, that’s what crystalized in my mind. But even before then, the phenomenon was clear, I just didn’t have a sure way to describe it.

In the book, you wrote that the definition of civility that dominates American political discourse is “I can do what I want and you can shut up.” In news journalism, a similar principle is “balance.” How have these values or ideas been misused in the advent of Trump?

In the essay, I was trying to distinguish between civility as a form of mutual respect and civility as Donald Trump was using it; he was saying we need to stop the politics of personal destruction, which is most of what Donald Trump’s politics are. To the extent that two sides can have respect for each other, it’s about respecting the other side’s inviolable rights, and there’s no sense in which Donald Trump’s politics don’t allow for that. To the extent that you are relating this idea to civility to objective and balance in journalism, the problem is that those ideas have been replaced with being fair to both sides in a way that presents them as equally factual. Even as an opinion journalist, I try to give the facts as best as I see them, but I think in political journalism, you often get some version of "one side says the sky is green and the other side says it’s blue." I think that is in part a product of longstanding journalistic traditions regarding objectivity but also a lack of diversity in the newsroom that has led to certain ideas of what is considered objective is unchallenged.

The reason I asked is because the pull towards balance in journalism seems to have a way of policing civility in an asymmetric way. For example, during the 2016 campaign and Trump presidency, we saw a torrent of profiles from “Trump Country” but there didn’t seem to be any equivalent humanizing of Clinton voters in 2016 or Biden voters in 2020, and definitely not in conservative media. In the pull for civility or balance, it seems as if the news media can be a bit one-sided.

Certainly in 2015-16, we saw a lot of “souls of white folk” stories from newspapers trying to frame Trump’s rise in the most sympathetic manner as possible, but in 2020, if you’re reading The New York Times, you really did know that Black voters were the ones who rescued Joe Biden in South Carolina. So I would push back on that a little bit, in the sense that a lot of outlets did improve on their coverage of the Democratic Party and in particular, the Democratic Party’s base of Black voters who have typically chosen who becomes the standard bearer. But there are more axes of difference beyond the Left-Right worth exploring, and in some ways, political journalism does not always acknowledge those.

Your book is also coming out in the midst of controversy over critical race theory and teachers teaching students unfiltered American history. How do you make sense of this moral panic?

The critical race theory scare is a reaction to the re-evaluation of history sparked during the Obama presidency and the Ferguson protests. They sparked an inquiry into how we have a Black president but still have glaring racial inequalities that have not been resolved. That process was accelerated by the election of Donald Trump because he was so overtly running on the politics of white identity, and then it culminated in the George Floyd protests. That recognition frightened conservatives because the knowledge that racial disparities were caused through public policy, that implies the state should step in and fix it. If you are conservative and you believe that these inequalities are actually the result of in-born natural ability then you don’t want the state to do that. So I think there’s a recognition on their part that this re-evaluation of history would cause people to understand the lingering effects of racism in American life, and to prevent that, they want to make it difficult to teach history that includes the extent that discriminatory policies shaped racial disparities in America. This isn’t to say that everything taught in schools is correctly taught, but their larger argument is about it being wrong for the government to do anything about racial inequality because it would be unfair and interfere with conservative conceptions of liberty and individual responsibility.

During the Trump presidency, we often heard pundits from across the spectrum making the argument that “History won’t be kind to President Trump.” What is your take on this?

History is not a thing that operates on its own. It’s written by human hands and interpreted by human beings, and that interpretation is substantially mediated by power. For example, after Reconstruction, Democrats in the South saw Reconstruction as a mistake and saw Jim Crow as restoring the proper order of things. That interpretation was challenged by W.E.B. Du Bois and others but it did not begin to be overturned in American public memory until the around Civil Rights era. My book is an attempt to put down a historical record of the Trump administration to show it as I believe it really was; to prevent this kind of manipulation of history from taking place (although, I’m just one person). But the public memory of the Trump administration will be determined substantially by who holds power in the future.

Joshua Adams is a Staff Writer for Colorlines. He’s a writer, journalist and educator from the south side of Chicago. You can follow him @JournoJoshua