With most of her family in the United States, eight years ago Lucila Presa decided it was time to also make it her home. The 43-year-old now lives in Chicago, and while she knows she’ll ultimately return to Mexico, for now she’s focused on being an American.

For Presa, that means pursuing citizenship. She had been planning on naturalizing for some time, but the issue has become urgent. The reason? Donald Trump.

While the president-elect hasn’t spoken much on the more than 13.3 million documented immigrants, aka green card holders like Presa, he has said a lot about immigrants in general. And they weren’t nice things. Though permanent residents have secured the legal right to live in the United States, they’re not citizens—which means they do not have the full protections available to citizens, such as the right to vote, travel freely, obtain a U.S. passport or help relatives gain legal status. Most significantly, perhaps, documented immigrants are not granted full protection from deportation. Will their status become more precarious under an administration that has made no secret of its aversion to foreigners?

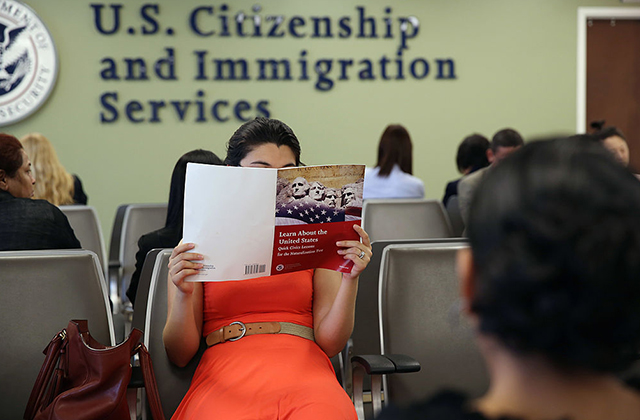

Presa thinks so. "We don’t know what Trump will do," she says in Spanish. "Even if we’re residents, maybe he can send us back to our countries." So she’s been spending a lot of time studying. The naturalization application process involves exams—and even many U.S.-born citizens would have to study hard to pass the civics portion, which includes questions on the Constitution, the branches of government and names of current representatives.

Aside from the tests, it is a tedious process for a number of other reasons. If an applicant is eligible, the federal government then vets the person via interviews and background checks. They meticulously piece through an applicant’s closet, eyeing any skeletons that may raise a red flag.

Though tedious and invasive, naturalization is the step that many choose. And, arguably, many more will choose it to protect them from possible crackdowns against non-citizens, both documented and undocumented. Under a White House that has promised to deport up to three million immigrants, naturalization can look significantly more attractive. It sure does for Presa—despite the hours she’ll spend studying in preparation.

To help those considering the process, Colorlines answers common questions about naturalization, what risks come with it and what may change under the Trump administration.

Should permanent residents, or green card holders, be concerned about Trump’s presidency?

Yes, says attorney Ann Cun, who has been working in immigration law since 2001 and currently runs her own immigration law practice in San Francisco, California.

Trump’s cabinet picks haven’t been very inclusive of particular groups in this country, she says. For example, Stephen K. Bannon, the president-elect’s chief strategist, is a White supremacist who has made negative comments about feminists, Muslims and #BlackLivesMatter. “[These statements] serve to divide our country,” Cun explains. “They also serve to make individuals feel that they are not true Americans, whatever that definition means to that particular individual.”

As Cun stresses, papers don’t matter if a policy targets individuals based on skin color. “Ultimately, what you’re going to have to defend against is the color of your skin or the scarf around your head.”

What about deportation? Should legal residents be worried about that?

Not yet.

Permanent residence, stresses Cun, is a privilege in this country—a privilege that can be revoked (somewhat like a driver’s license).

For now, green card holders could lose their residency and face deportation due to felony or violent crimes, Cun explains. While it is still unclear what specific policies the new administration will pass, we do know that Trump has promised to deport immigrants who have committed crimes. That would include permanent residents or any person who chooses to expose their criminal history through the application process.

In addition, legal residents can be deported for reasons some may find insignicant. These include checking off the U.S. citizen box on a form when they’re not; it’s seen as fraud. DUIs or DWIs, which could be a single lapse in judgment, Cun says, can result in a deportation. The possibility of a Republican-led Congress increasing the crimes that could lead to deportation is also a realistic possibility.

People who have lived legally in the U.S. for years or decades with their green card may feel like they’re citizens, forgetting that they’re actually not, says Melissa Rodgers, director of the New Americans Campaign with the Immigrant Legal Resource Center. “For many, the notion that they could be at risk of being removed from the country and not having the right to go back is not something top of mind for people. Only U.S. citizens could be really protected from deportation.”

Will the Trump Administration make it more difficult to naturalize?

Maybe.

Trump has been critical of the naturalization process in the past. During a rally in August, he warned about examples like the brothers who committed the Boston Marathon bombing and the couple behind the San Bernardino mass shooting. More recently, he tweeted that Ohio shooter Abdul Razak Ali Artan, who was a legal permanent resident, "should not have been in our country."

Trump has not laid out specific plans, but Cun does imagine that the administration will try to make the naturalization process more difficult by increasing eligibility requirements. For example, one current requirement to naturalize (not through marriage) is, according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (U.S. CIS) website, that the person has been physically present within the U.S. for at least 30 months out of the five years they need to be here to file their paperwork. (See the U.S. CIS website for details.) Cun expects him to lengthen the 30-month period.

Cun also foresees an increase in the current application fee of $595. While it is scheduled to rise to $640 beginning December 23, she imagines a more significant hike in the next two to three years. The U.S. CIS’s fee waivers for low-income people could also be in jeopardy, Cun says.

Where can people find more resources to help them decide if naturalization is the right decision for them?

The process currently takes about five to seven months, says Joanne Ferreira, a spokesperson for U.S. CIS. So if you already know you want to naturalize, get on it. If you’re on the fence, Cun suggests that you be patient until you know.

To help you figure it out, here is a list of resources, including immigration attorney contacts and official governmental forms:

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services

Here, you can download forms, find out eligibility requirements and get in touch with someone from the department to answer any questions. The site also offers practice English and civics exams for those ready to take them as part of their naturalization application. - Immigration Legal Services Directory

This provides a state-by-state directory of immigration legal services. If you ever have questions regarding naturalization, you want to speak with an immigration attorney or an accredited community organization. Never look to notaries for consultation, as there is ample evidence of many scamming and robbing immigrants of their money. You can read more about that here. - Immigrant Legal Resource Center

Immigration attorneys make up this center and are eager to offer help. The website also provides various resources such as visuals for understanding what makes a person eligible for citizenship, naturalization fee waiver packets and a guide to applying for naturalization. - New Americans Campaign

This campaign is made up of local organizations and lists them on their site so that residents can reach out. People looking for help can also find resources in large print for those who need it, as well as videos.