On January 15, 2019, Andrea Circle Bear, then age 29, was sentenced to 26 months in a South Dakota federal prison for using her home on the Cheyenne River Sioux Indian Reservation to sell methamphetamine. In a press release about her sentence, U.S. Attorney Ron Parsons said, “Don’t let yourself or your property get mixed up in the world of illegal drugs. It ends badly.”

Andrea Circle Bear’s life ended as a result of COVID-19, while she was in custody and less than a week after she gave birth via cesarean on a ventilator, making her the first female federal prisoner to die as a result of the disease. As of April 21, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) said that 4,893 cases and 88 deaths have been reported among incarcerated and detained people, and 2,778 cases and 15 deaths among staff members.

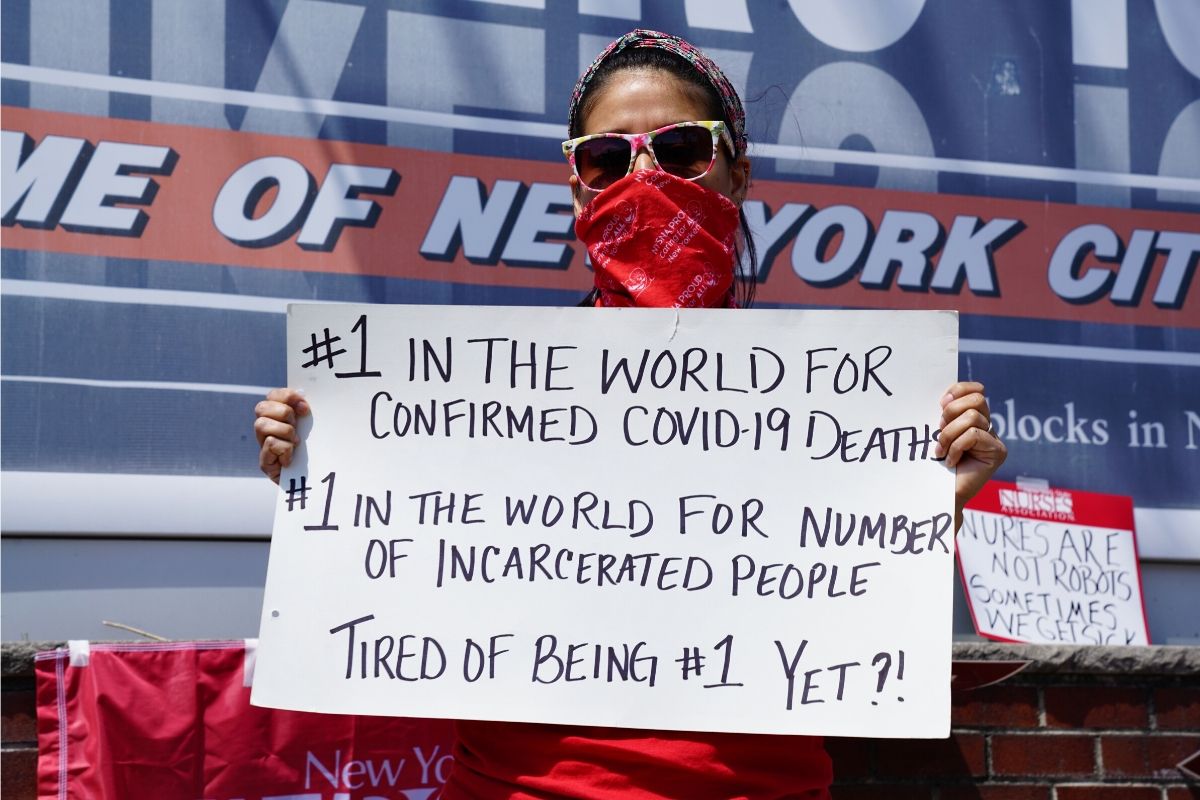

With almost 2.3 million people locked up in 1,833 state prisons, 110 federal prisons, 1,772 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,134 local jails, 218 immigration detention facilities, and 80 Indian Country jails, families and advocates are on heightened alert, especially during the novel coronavirus pandemic.

“I can only imagine how hard it is for our incarcerated relatives to cope with fears of COVID-19 and the coping isn’t just internal to prisons and jails,” said the chairman of Huy, Gabriel S. Galanda, who is also an Indigenous lawyer in Seattle. “There’s an external component in terms of how loved ones are faring.” Huy is a tribally-owned, nonprofit that provides educational, economic, religious and rehabilitative support for American Indian, Alaska Native and other Indigenous prisoners throughout the United States.

In addition to mail deliveries being put on pause for some time and not being able to fund beading and sewing projects (even for personal protective equipment), Galanda said that he has to trust his state will do the right thing by those incarcerated—at least physically. Galanda also noted that now is Pow Wow planning season, a period crucial to the area tribes’ cultural and spiritual practices, but that the 12 prisons across Washington state that usually participate won’t at this time.

“Spirituality and religion in our work have been how our relatives are most able to heal, atone and learn from mistakes they’ve made,” Galanda said. “We’ve felt helpless from the outside looking in, unable to help our families relatives in all the ways we typically help.”

Roanoke, Virginia, resident Casandra McNeil, whose husband is in Nottoway Correctional Center on a 15-year sentence in which he’s already completed 10 years, said that both she and her 16-year-old daughter are worried because of health issues that grew from injuries he sustained when younger. “He suffers from shortness of breath and he gets respiratory and sinus infections pretty often too,” McNeil said. “His health conditions really put my husband at high risk, more so than other people.”

Even though McNeil said she is able to speak with her husband several times a day every day, she said that he is not being isolated because of his preconditions. Instead, McNeil said that there are often multiple people in one small space, including guards who are not wearing masks.

Advocates have already sounded the alarm about the prison industrial system during COVID-19. The Prison Policy Initiative published the action plan “Five Ways the Criminal Justice System Could Slow the Pandemic,” which includes making all phone calls free and video chats accessible. MomsRising recently wrote to governors, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to release everyone who isn’t a public safety risk and to ensure healthy hygiene and access to medical care for those who remain incarcerated. Highlighting Circle Bear, vice president of MomsRising and prison reform expert Monifa Bandele said that prison was physically and emotionally taxing before the pandemic, and it’s literally deadly now.

“It’s impossible to follow CDC rules to protect yourself inside,” Bandele said. “Not only can’t you social distance, but you are being housed in a place where sanitation and hygiene aren’t available. They don’t have access to open water throughout the day. As difficult as it is for us to get tested, they don’t have access to testing. No social distancing and hygiene is a disgrace.”

What’s more, Bandele said, it’s not just people who are incarcerated who are getting sick, it’s workers within the prisons and jails who become potential vectors. “There’s an ecosystem that’s connected to prisons that fuel the environment of the community and people—food workers, administrators, healthcare—come in and out of these prisons all day,” said Bandele. “So if you have a hotbed, it will infect the surrounding communities.”

This ecosystem is what McNeil worries about. “COs also put people in prison at high risk, because they are exposed to the outside world and come into work,” she said, “so they’re more susceptible to spread it than inmate-to-inmate.”

McNeil’s fears aren’t unfounded. ABC News reported on May 5 that over 5,000 federal and state correctional officers have tested positive for COVID-19. “If you look at how it’s tracked across the globe, you’ll see that this thing runs through a correctional facility like a brushfire, and it doesn’t stop until it runs out of people, basically,” Andy Potter, executive director of the Michigan Corrections Organization, told ABC.

To help allay some of the fears that families of the incarcerated are facing during the pandemic, Democratic leaders of the House of Representatives introduced the Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act on March 11, which includes the “COVID–19 Compassion and Martha Wright Prison Phone Justice” bill. Named after Martha Wright, who for 10 years fought for fair phone calls for the incarcerated, the bill would put price caps on all forms of communications to and from prisons and jails across the country. In April, Colorlines reported that the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) would make prison phone and video calls free.

“All charges, practices, classifications, and regulations for and in connection with confinement facility communication services shall be just and reasonable, and any such charge, practice, classification, or regulation that is unjust or unreasonable is declared to be unlawful,” reads part of the bill.

As the more than $3 trillion HEROES Act makes its way to the Senate and then hopefully to the White House, advocates have responded. “While this kind of legislation was sorely needed before the pandemic, the suspension of visitations and the rapid spread of the virus in prisons, jails and detention facilities have made the status quo untenable,” Free Press Action vice president of policy and general counsel Matt Wood said in a statement on March 12. “People who are incarcerated and their families must have access to communications services at just and reasonable rates. This bill would give the FCC the authority to take action.”

Advocates and families are still pushing for policies that would prevent another Andrea Circle Bear tragedy. The fact that Native Americans are incarcerated at a rate 38 percent higher than the national average and Native American youth are 30 percent more likely than Whites to be referred to juvenile court than to have charges dropped, is something that keeps Galanda awake at night

“Congress should take any opportunity to consider or cause the early release of populations who are of low recidivism risk, especially those who are disproportionately incarcerated,” Galanda said. “This is also an opportune time to release prisoners who are down on a life-without-parole sentence for a mistake they made as juveniles. The Supreme Court has already declared such sentences unconstitutional as cruel and unusual punishment.”

Bandele, whose organization released a statement on May 13, agreed. “The HEROES Act will help tremendously, including by extending paid leave and sick days,” she said. “But, it falls short with regard to creating more pathways and funding to reduce incarceration, which is critical to public health.”

To learn more about the HEROES Act, click here.