A new report from nonprofit advocacy group Vera Institute of Justice breaks down how many teenagers of color are shuttled into the criminal justice system. Penned by Mahsa Jafarian and Vidhya Ananthakrishnan, “Just Kids: When Misbehaving is a Crime” delves into the world of “status offenses”—behaviors like skipping school or running away that are deemed illegal only because of the age of the participant and that are overwhelming responsible for landing children of color in the justice system at disproportionate rates.

The authors highlight how actions that are typically understood to be normal adolescent behaviors are frequently interpreted as illegal for kids who are already on the margins of society, with authorities overlooking important underlying issues that could be addressed with interventions. From the report:

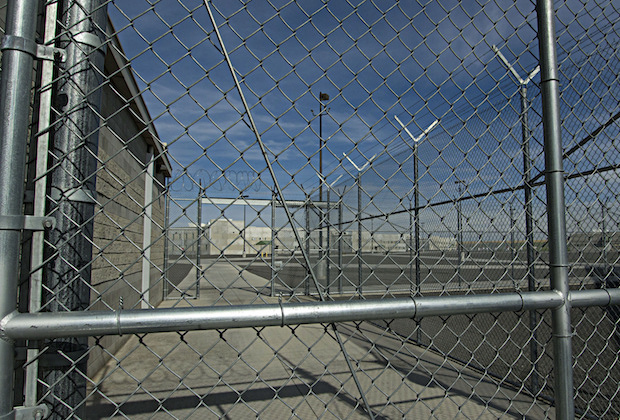

Such a punitive approach has detrimental consequences: it criminalizes kids for misbehaviors that pose little to no risk to public safety and may punish them for developmental changes and service needs that are beyond their control. It also disproportionately pushes kids into the system who are already underserved and more likely to be subject to biases and harsher discipline—specifically girls, kids from poor communities, kids of color, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and gender non-conforming (LGBT/GNC) kids. The justice system is not designed to support kids as they grapple with developmental changes or to address the underlying issues that may be causing them to “act out.” Instead, court involvement—and the incarceration that may follow—increases kids’ risk of engaging in future delinquent (criminal) behaviors and moving deeper into the system.

The report, which was released Monday (August 7), goes on to explore how bias factors into how officials interact with misbehaving children and the ultimate punishment they dole out.

Whether or not misbehavior lands a kid in court is largely dependent on the individuals who respond to the behavior and how they view the kid who is “acting out.” Be it a police officer, a school official, or even a parent, adults have varying levels of knowledge around youth development and particular ideas about what acceptable family and social norms look like. These understandings converge with their personal biases (including racial, cultural, and gender biases) to shape how they interpret and respond to a kid’s misbehavior.

Not surprisingly, these varying perspectives lead to disparate consequences for kids, especially girls. Early legal thinking considered boys delinquent if they violated a civil ordinance or law, but girls were charged for general “immorality”—a broad term which included unruliness, associations with immoral persons, vagrancy, frequent attendance at pool halls and saloons, and profanity. That is, girls were punished for behavior that was considered “unladylike”. And, once in court, a higher percentage of girls were sent to reformatories than boys. While these disparate laws no longer exist, girls today are still typically sent to the justice system for less serious offenses (status offenses and technical violations) than boys, and they are more likely to be detained and stay in juvenile justice facilities longer for those minor offenses.

Unsurprisingly, the same discrepancies exist when looking at poor kids, kids of color and LGBT/GNC kids. Including girls, these kids are most likely to have limited access to programs that meet their service needs and be subject to biases that lead to harsher reactions to their misbehaviors. For example, schools with more Black students are more likely to suspend and expel kids for “acting out,” while schools with fewer Black students are more likely to respond with behavioral treatment and special education programs. Research also indicates that police officers tend to view Black kids as less innocent than kids of other races, and teachers tend to view Black girls as louder, more unruly and more in need of reprimand for being “unladylike” than other girls. And, kids who identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual are more likely to be stopped by police, arrested, and convicted for engaging in the same behaviors as their straight peers.

In other words, kids who are already less privileged—in how they are perceived and in their access to services—are more likely to have their misbehavior criminalized.

The report concludes with recommendations for keeping children out of the juvenile justice system. Key takeaways:

- Approach all misbehaviors with an understanding of youth development and needs

- Eliminate court as an option for status offense cases

- Understand kids and families as central to the solution

- Develop a robust continuum of services that can meet the needs of youth and families in their communities

- Measure and publicly report on the efficacy and fairness of status offense systems

Read the full report here.