The 2020s roared in with a teachable moment for the nation—that white supremacy and law enforcement are inextricably linked. Recently, an independent panel of medical experts and legal professionals released a 157-page report on February 21 reviewing the 2019 death of Elijah McClain by Colorado police and wayward paramedics, stating that the “facts trouble the Panel,” while not blaming either.

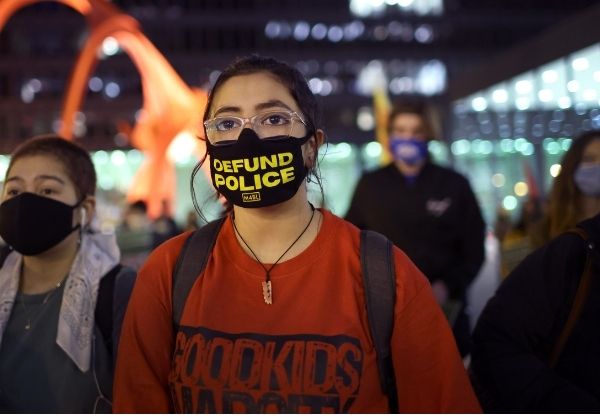

While the push to defund the police and hold them accountable has been adopted in different parts of the country, including the introduction of new legislation from Congress with the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act of 2020, activists are skeptical.

“The initiatives [in the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act] provide more resources to the police that do not speak to the size, scale and scope of police and policing,” said Karissa Lewis, the national director of the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL). “It does not go far enough in the perspective of the Movement for Black Lives. At its core, it moves more money to policing, but it doesn’t look at the various ways that police forces have been militarized.

That’s why M4BL introduced the BREATHE Act, to remove law enforcement from schools and instead dispatch trained trauma interventionists and 911 mental health experts to an unarmed person who might be having a mental health crisis, rather than the police. The BREATHE Act, Lewis says, has already gained some traction since it was introduced last July. Lewis explains that it’s been partly implemented in states like Illinois, which also introduced a bill earlier this year called the “Deaths in Custody Act,” which states that law enforcement agencies must report any deaths that have occurred under their watch. In addition to Illinois, Lewis said there are other states and municipalities that have heeded M4BL’s call for reduced policing.

“Over the last year, there has been a divestment of over $840 million from police departments and an investment of at least $160 million in communities across the country, as well as canceled contracts for policing in schools that have saved an additional $34 million,” said Lewis.

Lewis provided further insight that Madison, Wisconsin, ended their contract with the school police and Oakland, California’s Black Organizing Project won a campaign to eliminate the school police, which had its own independent police department.

“That’s the kind of accountability that we’re seeing and we’re going to continue to demand,” Lewis affirms. “We’re actually shifting the narrative for folks to understand policing and safety in our community.”

And it’s not only activists who have sounded the alarm in favor of police reform. The American Medical Association (AMA) published a statement that the “AMA policy recognizes police brutality as [a] product of structural racism,” and make clear that police brutality and racism directly affect the health of those who identify as BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, people of color).

“[White supremacy] is deeply ingrained [in policing] and ingrained with racial capitalism because policing’s main role is to protect capital,” Lewis said. “All the systems are interlocking and we have to do the work to dismantle these systems of harm collectively. What I’m naming is folks’ ability to think beyond the world of policing, which gives them space to then act towards a world without policing.”

Both Lewis and Kirk Burkhalter, a professor of law at New York Law School, believe that another way to think about accountability when dealing with racist policing is to think bigger than the law enforcer who committed the crime and to review the larger system.

Burkhalter served as a New York City Police Department (NYPD) officer for two decades, and his father and brother were also NYPD. “I’m assuming that Derek Chauvin will be convicted in some way, shape or form, but I am concerned that will let people off the hook,” Burkhalter said. “It’s very difficult to look in the mirror and say, ‘Wow, I’m part of the problem.’” “It’s much easier to see someone else and say they are part of the problem. Chauvin, what occurred, is symptomatic, not simply what’s wrong with policing. It’s symptomatic of what is wrong with our country. The fact that we still have failed to recognize the psychological, social and long-lasting effects of the vestiges of slavery. And until we come to terms with that, we’re not going to move forward.”

To help hold police accountable, Burkhalter is the director of the new 21st Century Policing Project at New York Law School, which seeks to create sustainable police reform with literal boots on the ground. When the project announces its launch at the end of March, Burkhalter said he hopes he can better prepare officers emotionally and intellectually to work with the public by training them with real academic rigor and pedagogy, before they’re released into the streets or an investigative room.

At the same time, the public can also do its part by pressuring its local, city and state legislatures to take real action against violent abuse. Police unions are mighty, Burkhalter said, because they have too much political sway, but that’s why normal taxpayers need to make their voices heard.

Racism and white supremacy may be inextricably linked, but with activists like Lewis and Burkhalter working to enforce police accountability across the nation, perhaps hope lies ahead.