In 2020 alone, police have killed nearly 600 people, according to Mapping Police Violence, with Black people killed three-times the rate of white people, even though Black folks are 1.3 times less likely to be armed. Last year, in a Pew Research Center survey, 84 percent of Black adults reported that they are treated worse than whites in the criminal justice system.

The current racial unrest holding firm across the nation as a result of the recent back-to-back police killings of unarmed Black people—George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, Tony McDade—and the call to reform policing policies is nothing new. In fact, police reform has been a topic for almost 100 years, as has abolition, the latter of which sociologist W.E.B. DuBois brought up in his 1935 book “Black Reconstruction in America 1860-1880.” But what is the difference, where does defunding fit in, and can the system be fixed?

“There are two particular things that I think are important to fundamentally change what’s happened with policing,” explained abolitionist M Adams, co-executive director for Freedom, Inc. and a leadership team member of the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL). “One, the defund strategy is smart because we need to shrink those budgets [by asking], what if we put that $100 billion in education, housing, healthcare? And reduce the number of people inside of that institution who can be organized enemies against us?” For abolitionists like Adams, defunding is a technique that will hopefully lead to abolishing the police.

Second, Adams made clear this movement is about self-sufficiency. “We are here to implement and to assert that we are going to be in defense of our lives and tear down anything that is not,” Adams said. “So the combination of draining the things that harm us, as well as building the power of things that will help free us, through our Black queer feminism, abolition, through our anti-capitalist politics, I think that pairing is going to make this win possible.”

This August, M4BL is planning a Freedom Summer project, inspired by the 1964 movement by Southern Black civil rights organizations to draw attention to violence being waged against Black Mississippians and their right to vote. This year’s Freedom Summer includes a six-week organizing intensive that trains and connects generations of freedom fighters to on-the-ground campaigns that are working on defunding, abolition and advancing electoral justice for all.

Reform Rewind

In 1967, following a summer of uprisings across the country, an 11-member bi-partisan National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (better known as the Kerner Commission) presented President Lyndon B. Johnson with a report explaining what happened during the unrest, why it happened and how it could be prevented from happening again.

{{image:2}}

Led by Illinois governor Otto Kerner, the nine white men, two Black men and one white woman wrote in the report:

Segregation and poverty have created in the racial ghetto a destructive environment totally unknown to most white Americans. What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.

And of police departments, the group said:

The Commission believes there is a grave danger that some communities may resort to the indiscriminate and excessive use of force. The harmful effects of overreaction are incalculable. The Commission condemns moves to equip police departments with mass destruction weapons, such as automatic rifles, machine guns, and tanks. Weapons which are designed to destroy, not to control, have no place in densely populated urban communities.

The Commission’s findings proved correct but because they were controversial, they were also ignored. With renewed calls to divest from feeding law enforcement’s budgets and to revise policies, some advocates are calling for reform while others are calling for the system to be abolished. But what is the difference?

Phillip Atiba Goff, professor of African American studies and psychology at Yale University and co-founder of the Center for Policing Equity (CPE), seems to stand somewhere in the middle. “I am a Black man centering Black communities,” Goff said. “That means abolishing systems of racial violence and reforming public institutions that can be made to reflect the full realization of Black freedom.” One reform idea, he said, is that law enforcement and advocates both want police to stay away from calls that don’t always require them, such as around substance abuse or mental health issues.

“The place where they disagree is on the size of the budget,” Goff said. “Ninety percent of what activists have been asking for is the same as what police have been saying for the last 25 years. But the way we line up, racism is somehow partisan in that we can’t hear the specifics of what people are asking for over their tribes, and that stunts our ability to move forward.”

Reforming Reform

“Police manage inequality by keeping the dispossessed from the owners, the Black from the white, the homeless from the housed, the beggars from the employed. Reforms make police polite managers of inequality. Abolition makes police and inequality obsolete,” human rights lawyer Derecka Purnell wrote in The Atlantic on July 7 in an op-ed titled, “How I Became a Police Abolitionist.” “Abolition, I learned,” Purnell wrote, “was a bigger idea than firing cops and closing prisons; it included eliminating the reasons people think they need cops and prisons in the first place.”

To that end, some have argued that reform is too ambiguous because departments aren’t a monolith. As of 2016, there were more than 15,000 law enforcement agencies across the U.S. and one city with multiple departments could have different training, rules or standards of enforcement across zip codes, including how they define “community policing.” Many argue that the data on policing is flawed because it comes from the police themselves, not from independent watchdogs. Others, like Purnell, say reform actually provides more resources for policing, under the guise of banning chokeholds, community policing investment and diversifying departments—none of which would have saved Breonna Taylor or Rayshard Brooks.

“There are some people who believe there is no need to have anyone with a badge and a gun; that the community can handle all of the things police get called to do” Goff explained. “It’s about changing the mission of the profession and how it aligns with the goals of the community and that’s not inconsistent with one version of reform. We need to reorder with the goal of centering our vulnerable communities.”

For Goff, that also means talking about the challenges of crime if we zero out police. Lots of people are incarcerated, he said, because they did something illegal. Advocates, like Adams, would argue that crime is a social construct that depends on race and class. An important point that both Goff and Adams agree on is that there are political forces and organizations, such as politicians who champion for more enforcement and some national labor unions, with purse strings that are more powerful than those fighting for reform. “The people whose job it is to say that law enforcement is the only answer have way more money than the other side,” Goff said.

Adams echoed Goff, calling the relationship between police unions and politicians a deadly “machine” that allows unions to donate to different political causes that in turn create resistance against reform. “It’s really important for people to understand that there is an organized, powerful, well-resourced and well-backed resistance against [Black people] that has the ability to legally use deadly force,” Adams said. And while Freedom, Inc. and M4LB support labor unions, Adams clarified: “We do not support any profession allowed to consistently harm, cause violence, or is able to murder Black people with impunity. And for that reason we are against the use, the tactic, the argument that they try to make, which is that people are justified in doing this and that a labor union is protecting them.”

To try and get around the bureaucracy of police unions and departments who don’t share their data a free crowdsource community launched the Police Data Accessibility Project in early May “to enable a more transparent and empowered society by making law enforcement public records open source and easily accessible to the public,” according to the group’s mission. Advocates, politicians and the public are beginning to find new ways to hold the police accountable.

The Police’s Political Power

The frustration in failing to reform poor policing can be partly blamed on their unions. “Police unions play a critical role here because they fight adamantly against the firing of any police officer,” said Adams. A 2020 analysis, published by the Marshall Project, found that of the nation’s 15 largest police departments, Memphis was the only city that had a Black union leader. Aside from the mostly all-white male leaders, unions can also wield powers over politicians. The New York Times reported that “higher membership rates among police unions give them resources they can spend on campaigns and litigation to block reform [and that] a single New York City police union has spent more than $1 million on state and local races since 2014.”

Colorlines recently reported that NYC’s Mayor Bill de Blasio finally agreed to cut $1 billion from the New York Police Department (NYPD)’s budget, seven years after promising real reform. Many New Yorkers may remember when the Police Benevolent Association (PBA), the city’s largest police union, literally turned their backs on the mayor at a funeral for two officers in 2014, after de Blasio expressed anger over Eric Garner’s killing by a cop—politically scarring him for years. Fast-forward to 2020, and Ed Mullins, president of the Sergeants Benevolent Association (SBA,) is so angry that he declared war on the entire city, tweeting (below) on June 2, “We will win this war on New York City.”

I Hear You. Never Give Up. pic.twitter.com/1AuXW4DlIi

rn— SBA (@SBANYPD) June 2, 2020

rn

This war against elected officials trying to hold police accountable appears to be a national trend, regardless of race. In January, ABC News reported that Black elected prosecutors across the country banded behind St. Louis circuit attorney Kim Gardner, who sued her city and its police union alleging racism, following several attempts to establish independent investigations of police-involved shootings, among other reforms. The suit, according to the Associated Press and ABC, said the St. Louis Police Officers Association "has gone out of its way to support white officers accused of perpetrating acts of violence and excessive force against African American citizens," namely, the 2014 killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown by former officer Darren Wilson. On July 30, news broke that Wilson would face no charges.

"As a reformer and Black woman, I represent a clear threat to the police union and political establishment that are determined to preserve the status quo in St. Louis—a status quo that benefits the few in power at the expense of the many," Gardner said in a statement with the lawsuit, ABC News reported in January. Seven months later in late July, Portland’s Mayor Ted Wheeler was tear-gassed by federal agents in Oregon, while on the frontlines of a protest, in which he called the experience “urban warfare,” according to the New York Times.

To try and hold police departments accountable, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act of 2020 on June 25 to limit qualified immunity—that public officials who violate civil rights, including law enforcement, can be immune from civil liability—racial profiling and a ban on no-knock warrants and choke-holds, as well as the creation of the National Police Misconduct Registry. Since its introduction, the bill has sat in the Senate, where Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said it would die. This is another example of why Goff made his comment about those backing law enforcement having way more money than the other side. Basically, the Movement should watch its back.

Abolish Is the Word

First introduced to the House of Representatives by Reps. Justin Amash (D-Mich.) and Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.), via Amash’s Twitter account, Senators Edward Markey (D-Mass.), Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Bernie Sanders (D-Vt.) pushed the “Ending Qualified Immunity Act” forward on July 1, “to eliminate qualified immunity and provide for accountability when public officials, including police officers, violate Americans’ constitutional rights,” read the bill. The legislation aims to amend Congress’ 1983 doctrine, which some say, including the authors of the act as they spell out in the proposed legislation, was created over the decades out of whole cloth.

This week, I am introducing the Ending Qualified Immunity Act to eliminate qualified immunity and restore Americans’ ability to obtain relief when police officers violate their constitutionally secured rights. pic.twitter.com/PiNYP8cX8i

rn— Justin Amash (@justinamash) June 1, 2020

rn

“Qualified immunity makes it almost impossible for a victim of excessive force by a police officer to hold that officer accountable in a court of law. That must end,” said Markey in a statement. “If we want to change the culture of police violence against Black and Brown Americans, then we need to start holding accountable the officers who abuse their positions of trust and responsibility in our communities. That means once-and-for-all abolishing the dangerous judicial doctrine known as qualified immunity.”

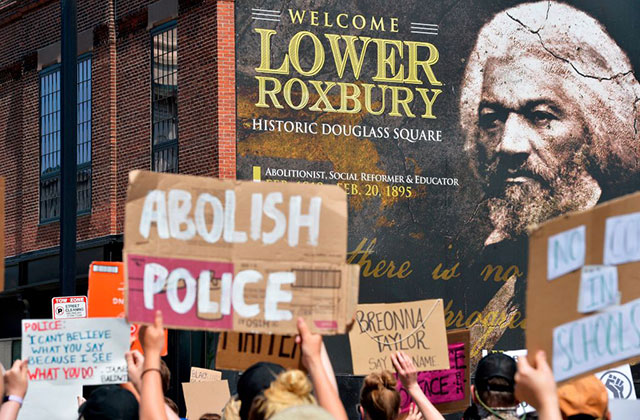

Like those who came before (Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman) seeking to end the systemic oppression of chattel slavery, Adams believes that we can abolish the police by solving the root causes of problems instead of using a culture of punishment to address them. “Which means as abolitionists, we are also not working to improve jails,” Adams said.

{{image:3}}

The abolitionist group #8toAbolition calls reform “dangerous and irresponsible,” and writes that reformers mislead the public by offering steps “that have already been tried and failed.” Abolitionists seek a world without police or prisons. To help policymakers better understand their budgets, CPE recently published a roadmap for funding public safety for cities that are looking to move money from one source, say policing, to another, perhaps mental health services, so they can visualize what that shift would look like.

“It’s not an endorsement, it’s how to put a map together,” Goff said. “When people look at it, they are astounded. They can look at the 911 survey, see what the resident needs and then look at where officers go. And most of it isn’t for violence. Looking at the roadmap, you get a magnitude of what you’re paying for.”

Yet for progress to be real and maintained, Goff is convinced that the nation will have to contend with its past. “While we stay focused on public safety—and that’s important—this about this country’s unaccounted for, unacknowledged anti-Black racism for 400-plus years that’s still in the making,” Goff said. “If we don’t think we have to atone for the way we’ve ignored and abused Black communities, we will keep paying this debt that is past due.”

Within the recognition of four centuries of oppression is also the understanding that Black people are functioning as a domestic colony, reinforced by law enforcement, said Adams. ”If we understand we’re in a colonial relationship with the government, then the role of policing for Black people has never been to protect and serve us,” Adams said. “It’s been to maintain the interest of the white capitalist elites. That is a function of policing.”