From a dead teen in Ferguson to poisoned drinking water in Flint, it seems as if the bad news keeps coming for Black Americans. But while it sometimes feels as if the collective weight has grown exhaustingly massive, this violence applied to Black bodies is not a new phenomenon.

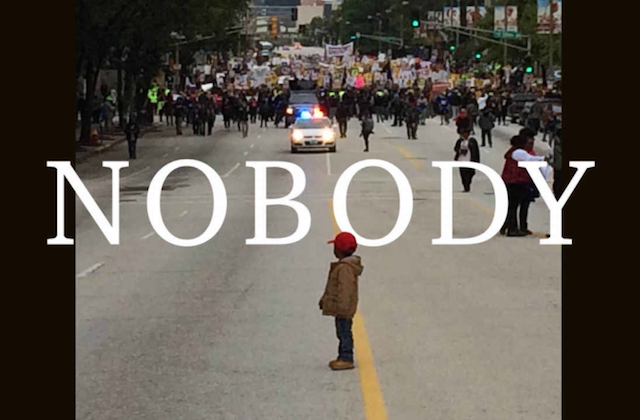

In his new book, “Nobody: Casualties of America’s War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond,” journalist and professor Marc Lamont Hill explores the historical conditions that got us here and makes explicit the ties that bind these events together.

Read these three key passages then get "Nobody" on Amazon, or better yet at a Black or independent bookseller.

To be Nobody is to be abandoned by the State. For decades now, we have witnessed a radical transformation in the role and function of government in America. An obsession with free-market logic and culture has led the political class to craft policies that promote private interests over the public good. As a result, our schools, our criminal justice system, our military, our police departments, our public policy and virtually every other entity engineered to protect life and enhance prosperity have been at least partially relocated to the private sector. At the same time, the private sector has kept its natural commitment to maximizing profits rather than investing in people. This arrangement has left the nation’s vulnerable wedged between the Scylla of negligent government and the Charybdis of corporate greed, trapped in a historically unprecedented state of precarity.

– –

There was not only Brown’s shooting to consider; there was also the aftermath. There was Brown’s body, left for hours on the hot pavement, his crimson blood puddling next to his young head, staining the street, flowing in a crisscross pattern, a tributary running slowly to the gutter. Eventually, an officer produced a bedsheet and placed it over Brown’s frame, a figure so large that the cover could not shield it all, the oversized teenager’s legs left peeking out from the bottom. Though it was early August, a wintry stillness set in over the next four hours, as police officers stood stone-faced and crowds of passers-by gazed in astonishment. While this was happening, Michael Brown remained on the street, discarded like animal entrails behind a butcher shop. As Keisha, a local resident who I interviewed a week after the shooting, said to me, “They just left him there . . . Like he ain’t belong to nobody.”

Nobody.

No parents who loved him. No community that cared for him. No medical establishment morally compelled to save him. No State duty-bound to invest in him, before or after his death. Michael Brown was treated as if he was not entitled to the most basic elements of democratic citizenship, not to mention human decency. He was treated as if he was not a person, much less an American. He was disposable.

– –

It would be easy, given the logic of the current moment, to individualize this crisis. We could say that our problems are the work of a few bad apples and that the great majority of police, prosecutors, politicians, corporations—indeed the great majority of the nation—frowns on the exploitation of the vulnerable. But, as I have tried to show throughout this book, such an argument is both untrue and largely irrelevant. Regardless of our individual or collective intentions, we are nonetheless bound up in a state of emergency in this nation. In order to repair the damage that has been done, we must craft a new set of frameworks for our economy, for our schools, for our justice system, for public housing. We must resist the power and persuasion of market values. We must reinvest in communities. We must imagine the world that is not yet.