The Kerner Report Called for More Black Journalists. Major Newsrooms Remain a 'White Man's World' [OP-ED]

"Shockingly backward." That's how the 1968 Kerner Commission report described U.S. journalism's representation of Black Americans. Formally the "Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders," the Kerner report indicted news media, along with police and politicians, for their role in driving the racial divisions that roiled the country in the late 1960s.

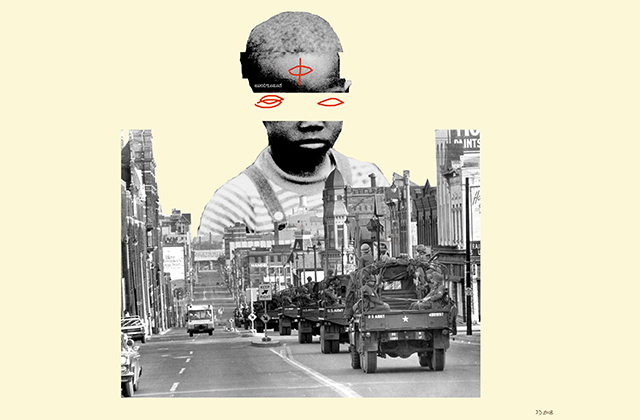

Kerner charged media with misrepresenting civil unrest in cities like Newark and Detroit, citing problems that will sound all too familiar: "scare" headlines, rumor relayed as fact, over-reliance on police and other official sources.

But the Commission declared these problems to be just part of a broader media failure "to report adequately on the causes and consequences of civil disorders and the underlying problems of race relations." And it linked this failure to the industry's abysmal record in "seeking out, hiring, training and promoting Negroes."

The need for more Black journalists seemed to be Kerner's takeaway; and numerous African-American reporters got their breaks in the wake of it. Veteran journalist Les Payne called the report and the protests that led to it "our affirmative action program." His contemporary Paul Block attests, "News hiring managers learned the only way to get the story and get close to what was happening was to hire reporters from those communities."

These reporters did groundbreaking work, not just on urban unrest and the "ills of the ghetto," but on everyday life in communities of color, filling a void left by a press corps that, Kerner charged, "acts and talks about Negroes as if Negroes do not read the newspapers and watch television, give birth, marry, die and go to PTA meetings."

But hiring flagged. African-Americans were just 2 percent of newspaper employees in 1978, few in decision-making roles, and two-thirds of the nation's papers had no employees of color, according to a survey by the American Society of Newspaper Editors (ASNE). The group called for the re-ignition of Kerner's demands, setting a goal of minority employment in newspapers equal to their proportion of the country's population by the year 2000.

By 1998, it was clear this was nowhere close to happening—Black people were 13.3 percent of the population and still just 5.4 percent of newsroom employees—and the goal was pushed to 2025.

In 2017, ASNE found just 5.6 percent of newsroom employees were Black, and 4.6 percent of newsroom leaders. Black people were just 5 percent of TV news directors in 2016, according to the Radio, Television, Digital Association, just 3.1 percent of radio news directors. Existing research suggests that "new" media are not new in this regard.

ASNE's statement on Kerner's 50th anniversary inadvertently names the problem: "The 2000 goal was not met," it reads, "but 'diversity' is now part of industry language, and outreach efforts continue."

But that's just it: The Kerner report didn't call for "diversity." It called for U.S. journalism to de-center its White male view. Media "report and write from the standpoint of a white man's world," the Commission declared; coverage "reflects the biases, the paternalism, the indifference of white America." This is not merely lamentable; it is “not excusable in an institution that has the mission to inform and educate the whole of our society.”

For Kerner, the meaningful representation of Black people in editorial roles was not a sop, or a nicety, but a core value. It recognized that media's White supremacy problem couldn't be solved with a few sensitivity seminars. Inclusion was crucial as a means toward an end—media that would "meet the Negro's legitimate expectations in journalism."

If the media industry has fallen short in Kerner's goals for hiring and retaining journalists of color, that has much to do with its failure to take seriously that more radical charge.

We see that failure all around. It's there in the contrast in corporate media's depictions of Black and White protestors, or their compassionate coverage of opioid addiction among White people compared to their pathologizing treatment of crack cocaine, or their “balancing” bogus charges of voter fraud with documented evidence of voter suppression.

Above all, it's reflected in elite media's continued disinterest in confronting the forms of institutional racism—redlining, job discrimination, over-incarceration —impacting African Americans as crises, rather than simply stories to (sometimes) cover. The problems that send Black people into the street, Kerner famously stated, are not "just another story."

Was Kerner hopeful, or naive? At one point, the authors nod parenthetically toward "pressures—competitive, financial, advertising," that "may impede progress toward more balanced, in-depth coverage and toward the hiring and training of more Negro personnel."

Here they severely underestimate the ways in which racism is baked into what are less “outside pressures” than the driving forces of commercial media. Consider the policy of "discounting": In a system where ad dollars are lifeblood, sponsors maintain their right to pay less for ads on stations that reach primarily audiences of color, regardless of their economic status. Consider an industry-captured FCC, spurring concentration that raises insurmountable barriers to Black ownership, while simultaneously, through its attack on net neutrality, working to shut down the ways people of color have found to communicate around Big Media via the Internet.

If, as reporters and audience, Black people are moving away from corporate media to Black, independent and social media, it's because they increasingly recognize that only a different structure of ownership and accountability will really allow for media that fairly reflect the full humanity of people of color, or that tell the hard truths that the present moment demands.

The Kerner report is far from perfect in its approach or recommendations. But in its recognition that Black people have legitimate demands of journalism that journalism fails itself and society by ignoring, Kerner was a call to action that is undimmed in urgency 50 years later.

Janine Jackson is program director at FAIR, the media watch group, and producer/host of the radio show "CounterSpin."