Before New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio committed to closing Rikers Island Correctional Center, Kalief Browder’s suicide or even the public acceptance of “mass incarceration” to describe the disproportionate sentencing of Black and Latinx peoples, Liza Jessie Peterson confronted the carceral state’s racist reality head-on when she arrived at the jail in 1998 to teach poetry. A decade later, she started a new challenge when she took on a position as a full-time teacher of 16- and 17-year-old boys incarcerated at Rikers.

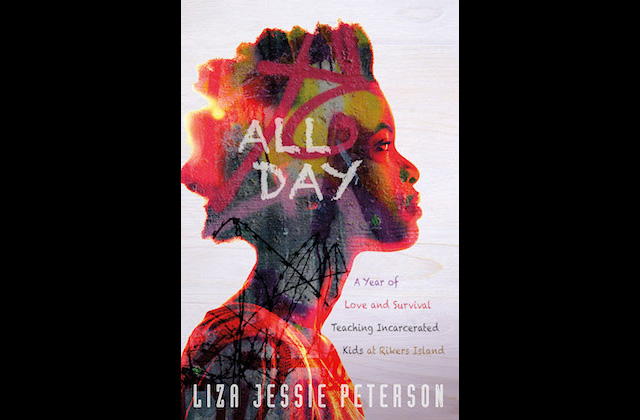

The poet and playwright catalogues her first year of teaching these predominantly Black and Brown youths in her new book, “All Day: A Year of Love and Survival Teaching Incarcerated Kids at Rikers Island,” which is available today (April 18). Built on her journal entries from that period, Peterson does not shy away from portraying her most difficult interactions with her young students, candidly discussing her impromptu strategies for maintaining classroom control (including adapting looks and tones of voice that will be familiar to any teacher, regardless of environment) and acknowledging negative feelings towards the most disruptive students.

But Peterson’s ultimate message is one of affirmation and humanity. She identifies with her students, and readers witness her pride when she gets students to think outside the box, such as when she gets students to write letters to the then-recently-elected president Barack Obama. They also experience her anger at the systemic barriers imposed on her students, like when she finds out about new rubrics that mandate teachers use a formulaic model in their classrooms that she finds overly restrictive and punitive. The book also features tremendous levity, as Peterson recounts everyday classroom antics with humor. “All Day” seeks to give incarcerated Black and Brown youth the same compassion routinely given to White teenagers—one that understands and forgives adolescence’s inherent temporary chaos instead of pathologizing it.

We spoke to Peterson about the development of "All Day" and her thoughts on the planned closure of Rikers. Here’s that interview, edited and condensed for clarity and length.

Why did you choose to write this book?

I would come home from work everyday totally mentally, spiritually exhausted from dealing with teenagers and being in that crushing environment. All I could do was write in my journal about what happened. So when I finally looked back at my journal, everything was so clearly documented. I laughed so much when I was reading my journal entries, over the classroom antics that just tickled me. I wanted to highlight my students’ humanity and adolescence, because Black and Brown boys are so hyper criminalized, and my experience with them was so raw and funny. As troubling as it was to see kids incarcerated, I was able to tap into humor to see through to their humanity. I don’t want to make light of it, but it wasn’t just this “Woe is me, I have to save these children” thing. It felt like how I cut up with my family. So I wrote the book because I wanted to remind people that these are children, and to not lose sight that adolescence is a natural period of temporary insanity, no matter your race.

The public conversation about mass incarceration is very different from when you started teaching at Rikers. Did you feel like you had to catch up while you worked there?

Mass incarceration was not even a term that people were using. “Prison industrial complex” wasn’t in the zeitgeist. There wasn’t talk about incarcerated kids, private prisons or racial disparity. And I came into the system totally naive, having little of the information that I have now. There was a disconnect between what I knew about prison and how I understood its affect on my community—Junebug sold drugs, so Junebug got locked up. I didn’t have the language and information to understand what was happening to my community until I stepped onto Rikers. And seeing the same Black and Brown faces, every month, day, year—you could count the White boys on one hand—and you knew something wasn’t right. It wasn’t until I started doing research on my own during the first year that the rabbit hole opened up to this diabolical system’s truth. And I saw that this is a monster, that it is slavery. It lit a fire in me.

What was the biggest institutional change that you witnessed during your time at Rikers?

Definitely the elimination of “bing,” Rikers’ term for solitary confinement, for adolescents. When I was there, it was commonplace that a kid would spend 60 days or more in the box.

What do you make of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s recent pledges to close Rikers Island within the next decade, or the recent state legislation to end prosecution of 16- and 17-year-olds, like many of your students, as adults?

Public outcry and protest moved the needle. Kalief Browder was the catalyst for all of this, and his death was a call to action. I know it is possible to close Rikers Island, and even just having the closing out there as a narrative, people are starting to reimagine life without Rikers. In that respect, I think there’s been a major psychic shift. Now, de Blasio put forth this idea, and we don’t know what the next administration will do. But now that the idea is in people’s psyche, conversations on how to move forward from Rikers have never happened on such a big scale. It’s not a grassroots conversation anymore, and something is moving.

“All Day: A Year of Love and Survival Teaching Incarcerated Kids at Rikers Island” is out now via Center Street.