Native St. Louisan Johnetta Elzie, 25, will always remember Michael Brown’s blood on the ground. "It was very intense, almost like someone took a paint brush and just painted the street with his blood," Elzie says of what remained of unarmed 18-year-old Brown late on the evening of Saturday, August 9. "What in the world do you do when there is a dead black boy on the ground?" she had asked all evening before jumping into a car with her best friend and driving to West Florissant Avenue. After spending nearly every day and night of the past four weeks handing out food and water to protesters and providing tear gas cures like Maalox, milk and water, Elzie is still working that question out.

The only thing she knows for sure is that the time for reconciliation is not yet here.

"Mike Brown was murdered and none of these white officials have any answers for all these people who’re angry, hurt, sad," she says. "…Hell, I’m angry. The officials just don’t have any answers for anything. You can’t reconcile [or heal] when there’s no acknowledgment of anything that’s happened."

In the past few weeks, government officials have made what appear to be efforts at reform if not reconciliation: Following the FBI’s announcement of a sweeping investigation into Ferguson’s police department, Ferguson’s city council proposed municipal court reforms and a citizens’ police review board.

But is this enough to return Ferguson and greater St. Louis to a calm, new normal? Is it enough to help residents to heal?

Reverend Starsky Wilson is pastor of Saint John’s Church, a progressive church that hosted U.S. and Canadian activists who had arrived in Ferguson under the mantle, "Black Lives Matter."* Wilson is wary of what he sees as local efforts to rush reconciliation. "There’re people who want calm and quiet but who do not want peace or justice," he says. The danger in pursuing the former course is that, "when we move too quickly to reconciliation without also addressing truth, we [again] oppress people by calling on them to forgive before anyone has acknowledged their wrong."

For example, Wilson describes the reforms recently put forth by Ferguson’s majority white city council as, "potentially conciliatory." A response steeped in airing truths or acknowledging wrong, he says, would have enabled Ferguson residents to debate the proposals at the council’s first meeting since Brown’s fatal shooting. Instead, as reported by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the city council’s reforms were read directly into the record, leading to accusations that they had met in secret.

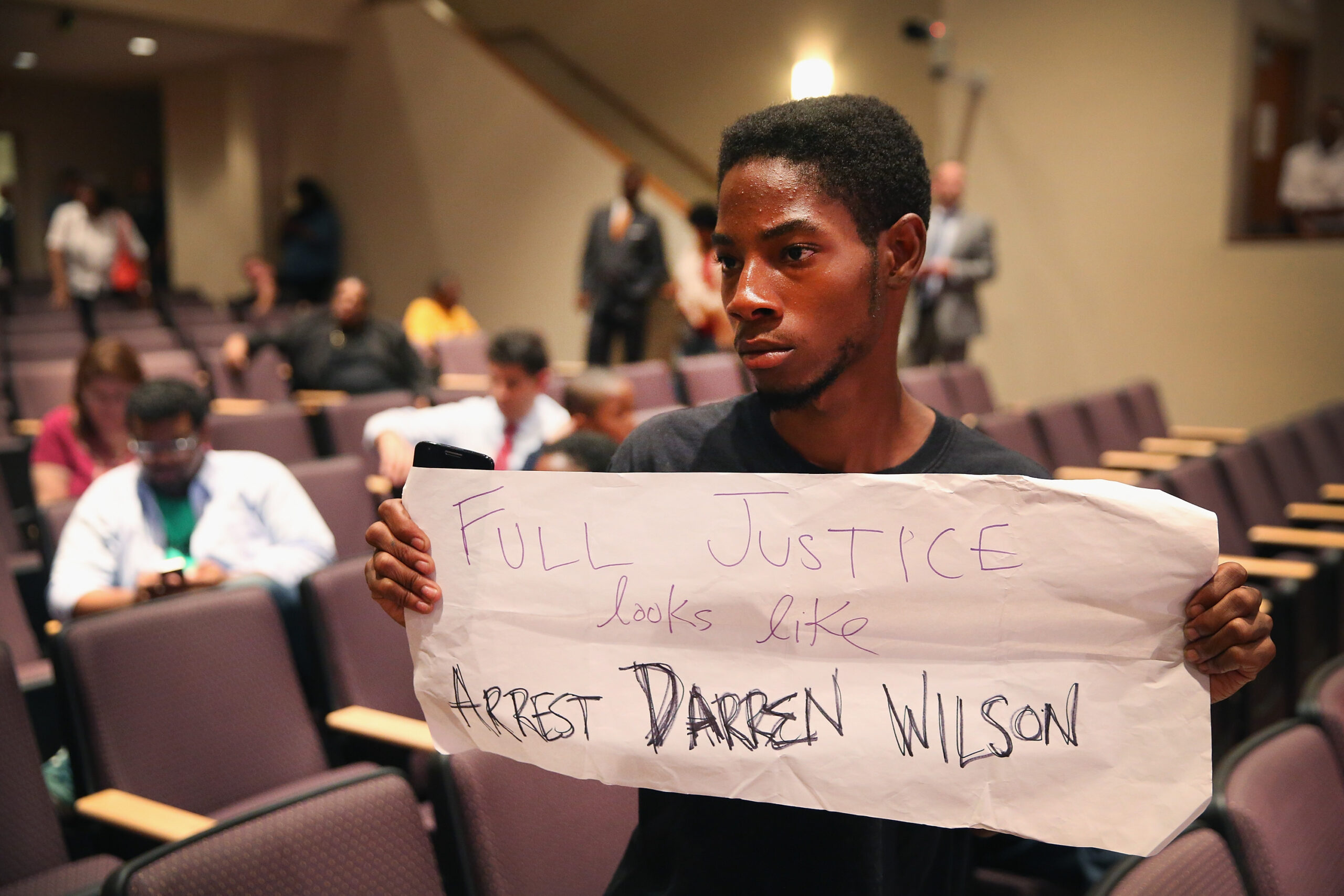

The simplest and arguably most healing institutional response Starsky says, would be the arrest of officer Darren Wilson. "He could be out on bail the next day, but an arrest at least acknowledges that something is wrong."

Another, longer-term institutional response for Ferguson could be to examine Cincinnati’s Collaborative Agreement, a document described as "the envy of black communities throughout the country." The historic pact instituted community policing and other reforms one year after the 2001 fatal police shooting of black, unarmed 19-year-old Timothy Thomas. His killing led to four days of unrest, martial law and a multi-million-dollar boycott of the city’s downtown. African-American leaders such as Rev. Damon Lynch III, pastor of New Prospect Baptist Church, Roselawn, and former president of the Cincinnati Black United Front, and former Black United Front member and Bond Hill business owner Iris Roley were so confident that the Collaborative Agreement improved their city’s racial climate that two of them traveled to a Ferguson rally and church meeting a few weeks ago and handed out copies to residents there.

"It took a long time and major sea change," Enquirer reporter Mark Curnutte says of the year of negotiations between city leaders, police, the American Civil Liberties Union and some of Cincinnati’s African-American leadership, "But the Collaborative Agreement has had such a positive effect on police-community relations."

"Obviously individual officers behave how they behave, but anecdotally community anger isn’t directed as frequently or as intensely towards the police department as it once was." says Curnutte, who was pulled off the NFL beat back in 2001 to cover the unrest. As the paper’s social justice and minority affairs reporter he’s a regular fixture in Cincinnati’s African-American communities. "I see a lot more interaction between officers on foot patrols and residents that are civil and positive."

Back in St. Louis, Rev. Michael Kinman, dean of the progressive Christ Church Cathedral, is looking at how to work for true reconciliation on an individual level, for both himself and his congregation.

"For us white folks, we can talk about peace and really want quiet. But how do we look in the mirror and ask, ‘How am I a part of the situation that’s gotten us to this point?’" says Kinman. Taking stock of how few black pastors he knows, Kinman adds, "Part of the challenge is that St. Louis is fragmented by design and that’s been an effective strategy for keeping poor people and people of color from power."

Kinman is spearheading an intense three-session gathering called "Facing Ferguson, Facing Ourselves." It’s for area leaders committed to challenging their city’s segregation.

From Elzie’s perspective, she might say that Kinman has a challenge ahead of him. She remembers going downtown at night for supplies while area residents were being tear-gassed. It struck her that some people were still barhopping and drinking while a tragedy was taking place just up the street.

"I went to Wash U to speak to a diversity group and a lot of them really didn’t know what was happening [in] Ferguson–which is only, again, 20 minutes away from that school," Elzie says. "But they just refuse to leave campus. It just blows my mind that people would be 20 minutes away and won’t go see for themselves what is happening."

A potentially frightening deadline adds a certain urgency to the community work being done by Elzie, Wilson, Kinman and many others: The grand jury is scheduled to decide whether or not to indict Darren Wilson in October or November. "I went to a [community] meeting on Friday and it was about 11 or 12 of us," Elzie says. "We literally went around the room asking, ‘How hopeful are you that the grand jury will indict ?" Only one person said, ‘Maybe there’s a chance.’"

"I don’t believe they will," Elzie says.

Update, September 16, 2014, 3:15 p.m. EST: The deadline for the grand jury decision, according to the Post-Dispatch, has been extended until Jan 7, 2015.

*Colorlines Editorial Director Akiba Solomon was a Black Life Matters rider, and Race Forward, Colorlines’ publisher, was one of many contributors to the rides.