On Tuesday Detroit News columnist Neal Rubin reignited a debate about Vincent Chin’s murder that’s as old as the case itself. Rubin wrote "What we all assume we know about the Vincent Chin case probably isn’t so," a column that attempted to revise the popular narrative of Chin’s decades-old homicide by claiming that Chin was not killed in a hate crime–as is widely accepted–but instead started and prolonged a bar brawl that just happened to end in his death.

Now, Advancing Justice-Los Angeles, an Asian-American civil rights organization, has spoken up to disagree with Rubin’s take on the case, and on Wednesday the Asian-American Journalists’ Association called on Rubin’s bosses at the Detroit News to issue a retraction. Rubin’s argument was buttressed by just one reporter’s take on the case, and was just irresponsible journalism, the AAJA argued. "Did anyone ask for fact-checking, context or balance?" the AAJA asked in its statement.

Stewart Kwoh, executive director of Advancing Justice-LA and the out-of-town counsel for the local Detroit group which fought for justice for Chin, wrote in a statement released Wednesday that Rubin should have called him for context:

I would have been able to tell him that our investigations identified a number of dancers who witnessed the racial epithets, all of whom provided testimony that was used in the first federal civil rights trial. (Rubin’s article names only one dancer.) Their accounts, as well as other eyewitnesses’, also indicated that Chin’s killers exhibited aggressively violent behavior, both inside and outside the bar. Rubin’s claim that Chin was the aggressor ("Outside, Chin attempted to prolong the fight") is therefore hard to believe.

Most damningly, Rubin gives short shrift to the fact that the first federal civil rights trial, tried in a Detroit court, with a Detroit jury, resulted in a conviction of one of Chin’s two murderers. The verdict was overturned on a technicality and a retrial was conducted, far away from Detroit, in front of an all-white jury in Cincinnati that absolved the killer. A more credible attempt at reexamining this case would have discussed these facts in greater detail.

Momentous periods in our history should be subject to reexamination, including the Chin case, since historical accuracy is critical to our understanding of who we are as Americans. But an effort like Rubin’s, marred by his failures and biases, is difficult to take seriously.

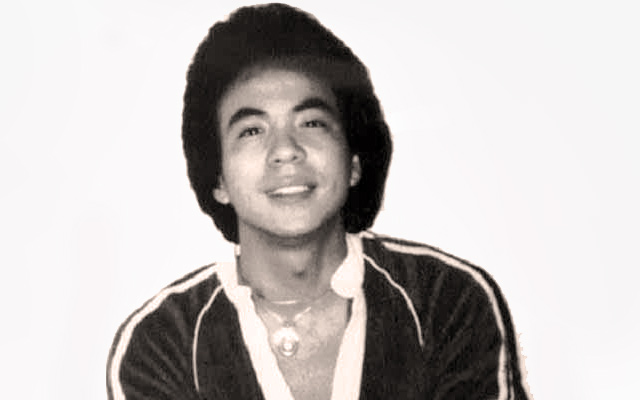

Indeed, the Vincent Chin case was a pivotal moment in Asian-American history. In 1983 Detroit, at a time of economic downturn and potent anti-Japanese sentiment, two white men named Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz thought Chin, a 27-year-old Chinese-American, was Japanese. In their mistaken racially motivated hysteria, they bludgeoned Chin to death with a baseball bat. Chin’s killers never went to jail for their crime, and that unsuccessful fight for justice galvanized Asian-Americans. The Chin case became a key chapter in Asian-American civil rights history.

Rubin’s version of the story is a serious challenge not just to popular understandings of an already controversial hate crime case, but also a real threat to closely protected narratives of Asian-American history. He should have known that wading into the debate with such an incendiary revision would require more diligent sourcing.