Nearly 30 years ago, in 1995, 28-year-old Pamela Jean George—a mother of two from the Sakimay First Nation in Saskatchewan, Canada—was brutally murdered by two white, affluent men, ages 19 and 20. The following year, MacLean’s reported that the men boasted about driving around, getting drunk, sexually assaulting and killing George. MacLean’s also noted that one of the murderers was even reported to have told a friend, “She deserved it. She was Indian.” For killing George, the two university students received manslaughter charges and were sentenced to 6.5 years in prison. They were awarded parole in 2000.

Investigative journalist Connie Walker, who is Cree from the Okanese First Nation in Canada, was in high school when news spread about George’s violent death. The murder took place not far from Walker’s reservation in Southern Saskatchewan.

rn

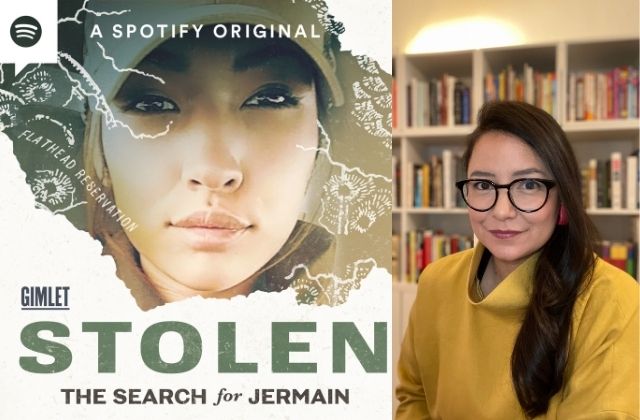

rn“I remember feeling outraged, sad, even hopeless when the verdict was announced, as I’m sure every other Indigenous woman and girl in the Province felt,” said Walker in her new Gimlet/Spotify podcast “Stolen: The Search for Jermain.” “Not only because of how the justice system devalued Pamela’s life, but because of what the judge, jury, media and society’s acceptance of this injustice said about how they valued our lives.”

Haunted by George’s murder, Walker ultimately focused her energy and career on investigating and reporting about missing Indigenous women. Walker has since tried to find answers for the disappearances or murders of six different women: Cleopatra “Cleo” Nicotine Semaganis (1974) and Alberta Williams (1989), both of whom she reported on in her “Missing & Murdered” podcast; and the others are Patricia “Trish” Carpenter (1992), Amber Tuccaro (2010); Leah Anderson (2013), and most recently, 23-year-old Jermain Charlo from Missoula, Montana, who went missing in 2018.

Across Canada and the United States, there has been a history of violence against Indigenous women that dates back 500 years when Europeans first arrived in both lands, and the violence has largely gone unchecked. According to a report published by The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), for American Indian Alaska Native (AIAN) women, aged 1-44, homicide was the sixth leading cause of death, based on data from 2018. In Oregon, the U.S. Attorney’s Office reported 13 missing Indigenous women as of September 2020. New Mexico is reported to have the highest number of missing or murdered Indigenous women and girls in the nation, with 78 cases, according to a December 2020 Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Relatives Task Force Report. Yet despite these findings, the data is often problematically inadequate.

This is why Walker is determined to find answers for Charlo’s family and others. To better understand the current situation and why there isn’t more media attention paid to this crisis, Colorlines spoke with Walker about her podcast, her research and what she’s learned from years of reporting on missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

Tell us about your research and how you tackle these cases.

The stories I focused on initially involved unsolved cases of missing or murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada, whose families were still searching for justice, still looking for answers. A huge focus of mine is to really try to go beyond the statistics. If you look at the statistics that are available, you will see that this is a crisis of violence that Indigenous women and girls are facing. In the reporting, it’s important to go beyond the statistics and try to show how every single one is a woman or girl who has a family, who loves them, and misses them and who wants justice for them. And that they are a part of a community. The podcast is really our attempt to give families a platform to share their stories of their search for justice for their loved one. And they deserve to have their voices and that search amplified. But Jermain is also a part of a bigger problem, in terms of the violence that Indigenous women and girls face in the United States and in Canada. And people need to understand where that comes from.

What have you noticed about these cases once they become public, and has anything surprised you?

I think that for lots of reasons, the conversations around Indigenous issues in general, and violence against Indigenous women and girls has been ignored, underreported or misrepresented in the media for a really long time. For decades. However, I feel like that conversation has shifted, maybe a little bit more quickly in Canada because we’re a smaller country. It was interesting to be a journalist focused on Indigenous reporting, in Indigenous communities, as that was happening because you really see how it was the individual families and grassroots activists who were pushing these stories forward, who were holding these memorial marches for women, advocating for families, and oftentimes, who actually had a personal connection to it. Many had lost somebody in their own family or they were searching for justice also.

Considering the lack of mainstream news around this crisis, where do you typically find your sources?

When I came to Gimlet, and to the United States to work on this new story, I knew that we needed to connect with those grassroots activists who were working in their communities. It really is these Indigenous women on the ground who are trying to prevent violence in our communities, who are the real experts and who are the real people who are advocating for and fighting for change. That was the initial place where I started to look. I learned about this organization called the Sovereign Bodies Institute, which is trying to create a database of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in the United States; and is also working to support families whose loved ones are missing, or who have been killed.[Sovereign Bodies tries to] help them navigate the system, which is really, really tricky.

rn

rnFor a lot of families, you hear over and over again about women who go missing and their cases aren’t taken seriously by police. Or families that feel like they have to organize their own searches or do their own investigations. [For the]e, people who are working in communities on a grassroots level– we’re trying to help them make that change. It was important for us to connect with them. That was really how I got connected with Lauren Small Rodriguez, who works with trafficking victims in Missoula, Montana. When you meet these women who are doing this work, the reality is that everybody knows somebody who’s missing, or has a story that deserves attention.

Why do you think families feel they have to form their own search parties to find their missing loved ones?

It’s really complicated and there’s no one answer. But just in general, in all of the reporting that I’ve done in Canada, in the United States, I think that there is a constant challenge that families feel they have to navigate around law enforcement and authorities to take their loved ones’ disappearances seriously. That is something that comes up over and over again. We talk about this in the first episode of “Stolen”. Her [Charlo’s] family was concerned immediately. A day without hearing from Jermain was a red flag for them. They were like, ‘She is always responsive. She answers her phone calls. She’s online all the time.’ For police, they will say that most missing adults are safely found within a couple of days. This speaks to the bigger issue from law enforcement’s perspective of not understanding the realities that Indigenous people, and women and girls in particular, face in the United States and in Canada. We’ve not been ignoring these stories; they’ve been so underreported in the media, that there is a lot we really need to make up for and understand.

Why do you think there’s such a void of information about what’s happening to missing Indigenous women and girls?

In terms of media, it comes down to representation. How many Indigenous journalists are in mainstream newsrooms? I feel I’ve been having the same conversation around diversity, inclusion and representation my entire career. In the first episode of the podcast I talked about Pamela George and the narratives in the media around her death—the way she was treated and juxtaposed to how differently that could have been [reported]. How that didn’t just impact Pamela, that impacted so many other Indigenous people in Saskatchewan and how all of these stories are continuing to perpetuate the stereotypes about what it means to be Indigenous, and there’s real harm in that. Until we better support Indigenous people in telling our own stories, that’s not something that we’re going to fix.

Have you noticed any parallels between George and Charlo’s cases?

I do and it doesn’t make any sense. Pamela was a woman from Saskatchewan. Jermain is a Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribal member in Montana. We all come from different cultures with different languages. The diversity of Indigenous people across Canada and the United States is incredible, whether you’re First Nations, Inuit, or mainly across North America. The unfortunate through line is that we’ve all been impacted by colonization, we’ve all been impacted by broken treaties, we’ve all been impacted by the institutional racism that led to things like the creation of boarding schools in the United States, or residential schools in Canada that separated Indigenous children from their families. These are shared experiences that Indigenous women have across North America, even though we come from different communities, different cultures, languages.

It’s devastating to know that one in two Indigenous women will experience some kind of sexual violence in their lifetime, and that over 80% experienced some kind of physical, emotional, or psychological violence. Those statistics are horrifying. When you think of the real people like Jermain Charlo or Pamela George, or Cleo Semaganis and Alberta Williams, it’s devastating to think that just being born an Indigenous woman in the United States makes them more likely to become a victim of violence. That is a reality that we need to acknowledge and understand before we can even think about addressing it.

What do you want the public to learn from the research you’ve done on Charlo’s case?

I hope that more people will be aware of who Jermaine Charlo is and to care about her and her family, who are devastated that she’s still missing and that they don’t have the answers they want about where she is. Our hope is that this leads to someone out there who knows something and it leads to some kind of positive resolution for the family. I would also like for people to understand that Jermain is one of thousands of Indigenous women and girls across the United States and Canada whose stories deserve to be told, and who face this crisis of violence in our communities that people have ignored or people have not paid enough attention to. We need to acknowledge it, understand it, and address it. And it starts with awareness. It starts with learning stories about people that you don’t know. And, hopefully, connecting with those stories.

rnListen to the trailer for “Stolen: The Search for Jermain,” here.

N. Jamiyla Chisholm manages creative content at Barnard College and is the author of the upcoming memoir “The Community.” As a journalist, she focuses on culture, gender and sexuality, and history.