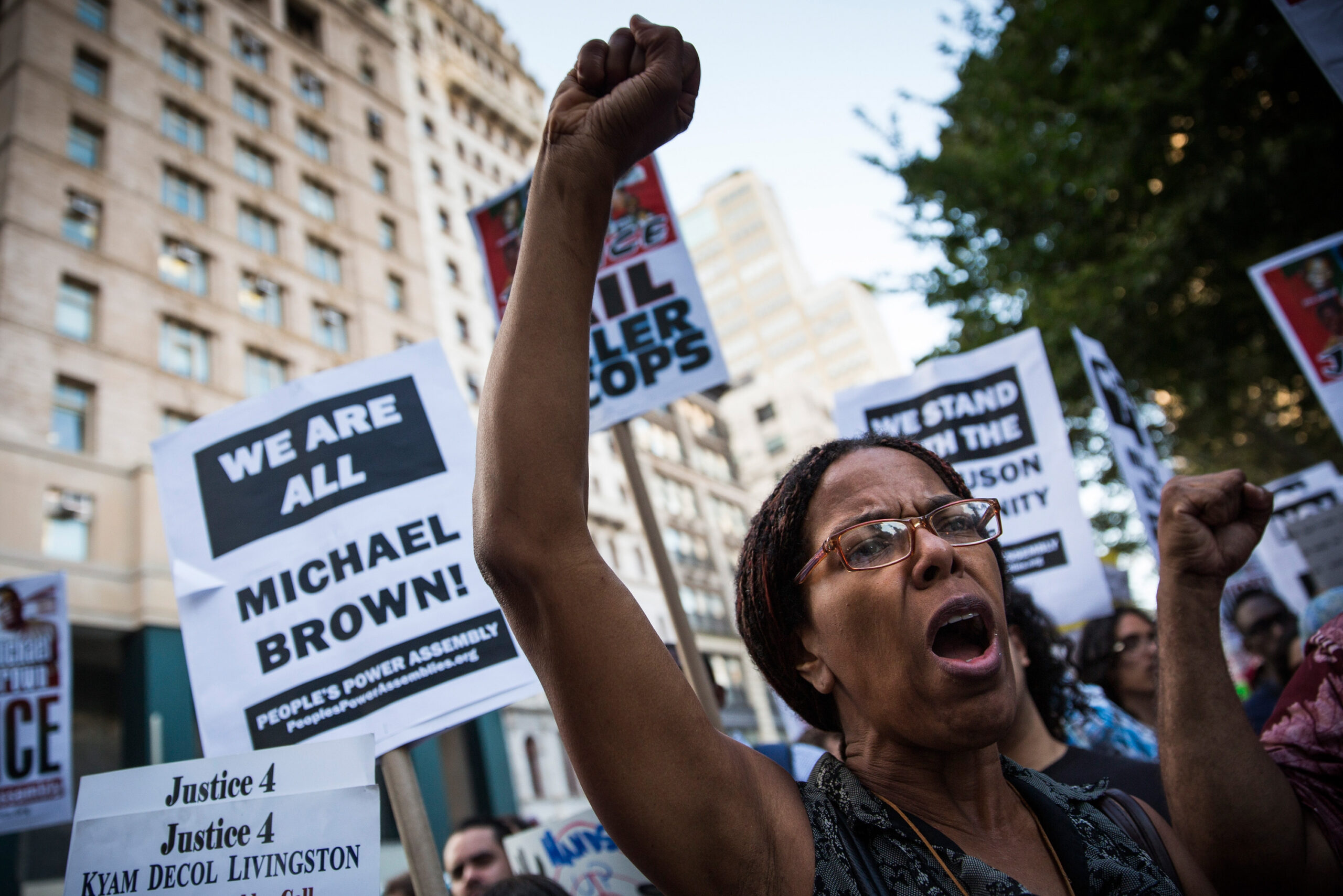

Here at Colorlines, the ongoing situation in Ferguson, Missouri, set off by the police killing of Michael Brown, has subsumed our collective attention and energy going on two weeks now. As the gender columnist, I decided to take a look at how Black feminists have been responding to the situation. While the issue of gender (beyond the policing of black masculinity and the crisis facing black men and boys) has taken a back seat in the mainstream conversation, black feminists have been keeping the intersectional analysis alive in their coverage and commentary. Here is a sampling of voices, including queer, trans and gender non-conforming feminist perspectives.

Professor Robin M. Boylorn, writing at Crunk Feminist Collective, expresses the difficulty of making sense of the situation:

I don’t know how to make sense of the possibility of Ferguson, the inevitability of Ferguson, the reality of Ferguson existing in the twenty-first century. We are living with retrograde racism the likes of which our parents and (great-) grandparents hoped to never experience again and prayed we would never experience. And I am struggling for words.

Every other day I learn another name I wish I didn’t know (Eric Garner, John Crawford, Ezell Ford) and add it to an ever-expanding list of black victims of police and vigilante violence (Jordan Davis, Tarika Wilson, Amadou Diallo, Rekia Boyd, Sean Bell, Yvette Smith, Trayvon Martin) because "truth is, we are all one bullet away from being a hashtag" (black women included). And that reality, and fruitless attempts to try to make sense of senselessness, means that Ferguson is not necessarily unique as a crime scene holding the dead body of an unarmed black teen, but it is a breaking point. Ferguson is our breaking point. The death of Michael Brown, emblematic of countless others, and the collective loss, grief and justified anger of people (of color and allies) who are tired of being terrorized and victimized by injustice requires that we say something. But I don’t know what to say. I don’t know where to begin.

Dani McClain argues at The Nation that the right to parent without fear of violence toward your child should be as much of a priority to the reproductive justice movement as access to contraception:

With this most recent killing, I am wondering what it would take for more people in feminist and reproductive rights circles to begin to think of parents such as Lesley McSpadden, Sybrina Fulton and Angela Leisure (a mother whose ordeal I’m especially reminded of in the wake of this latest tragedy) as women they advocate for just as passionately and vigorously as they advocate for a young woman’s right to contraception or an overwhelmed mother of three’s right to an abortion.

What would it take for the organizations and commentators who beat the drum for policies related to reproductive health and rights to use their platforms to advocate for black parents who lose their children to violent attacks on those young people’s lives? Gun control advocates reached out to Sybrina Fulton, Trayvon Martin’s mother, to make her an ally and spokesperson on efforts to repeal Stand Your Ground laws. It’s worth looking for similar areas of intersection within feminist circles or, even better, creating new initiatives that put these bereaved parents’ demands front and center.

Many have highlighted the extreme over-policing of Black communities, and the ideologies that undergird that crisis. Brittney Cooper, professor and co-founder of Crunk Feminist Collective, wrote for Salon:

We have a problem of overzealous policing in this country. That problem is exacerbated by issues of race and gender, so that black men are perceived to be far more threatening than they actually are. And when black women encounter police, we are not given the protections generally afforded to white femininity. Our womanhood does not mitigate the threat of police force. This, then, is not about the actions of a rogue officer, but rather about the ideology of overpolicing that deputizes extrajudicial behavior as completely justified, as long as the life being taken or haphazardly handled is a black or brown life. Though the killing of Brown by Wilson seemingly fits a long historical script of the harassment of black people at the hands of white police officers, the reality is that overpolicing is an ideology that many police officers subscribe to regardless of color.

That ideology is rooted in a kind of anti-blackness that sees black bodies as a perpetual and mortal threat.

And then there have been the perspectives of mothers themselves, and the heart-wrenching challenges they face explaining the situation, and their emotions, to their children. Feminista Jones, a blogger and activist responsible for spearheading the widespread August 14th National Moment of Silence in honor of Michael Brown, shared this story on her blog:

"Mommy, how come I can’t go with you to the rally?" my son, Garvey, tearfully asked as he said in the back of his father’s car. I’d just explained that it might not be safe for him to come with me, given the country’s sociopolitical climate during his moment of askance.

"It’s not safe," his father reiterated. "Let mommy do what she has to do."

"Baby, please know I’m doing this for you," I told him, trying to reassure him that everything would be OK and that mommy just had some work to do. He continued to cry, and I believe he understood as much as his 7 year-old mind would allow him to process in the moment of "I want my mommy."

In recent months, there have been entirely too many accounts of police officers in cities around the country using excessive force against civilians in ways that have led to severe abuse and even death. The stories of Eric Garner, Pearlie Golden, John Crawford, Marlene Pinnock, Denise Stewart, and 18 year-old Michael Brown have ravaged our hearts and stirred our souls.

Some have also highlighted what they see as a disparity between the attention given to the murders of Black men and the lesser visibility for the murders of Black women. Paris Hatcher, who works for Colorlines’ publisher, Race Forward, but is also the founder of a new, unaffiliated project, Black Feminist Future, had this to say about the situation:

It’s one of things where it’s so overwhelming. It’s like a flood of emotions every day. Ferguson is another indication of the status of black folks in this country. [I question] the increased visibility of this case and the lack of visibility of women who’ve been killed by police. I think these moments are incredibly sobering for what type of progress needs to be made. It’s just bare minimum that you don’t leave a person dead in the street for four hours. Sometimes it’s a little bit of disbelief, but then it’s like why are you shocked–you should understand by now.

When we talk about organizing a black feminist future, it’s a future where everyone in our community has the resources and access and power necessary to live and thrive.

The violence facing black trans women has also been emphasized in this moment of attention to Ferguson, and the connections between these acts of violence highlighted. The Audre Lorde Project, a "Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Two Spirit, Trans and Gender Non Conforming People of Color center for community organizing" in New York City released this statement uplifting the legacy of Audre Lorde, a critical black Caribbean lesbian voice:

We feel it is our responsibility and duty to make the connections between the murders of Black and Latin@ Trans women, the arrests and violations against LGBTQ youth of color, and the violent sexual and physical attacks against Trans men and women of color are an extension of the same conditions and systemic oppression.

These violent attacks lead to the brutalizing violence of (Non-Trans) men and women of color, and the detentions and deportations of immigrants of color. These systems were created and built under the false pretense of ‘protect and serve’ but instead are used to control and target our livelihood based on our race, physical ability, ethnicity, sexuality, gender identity, economic status and citizenship. The solutions to these acts of violence cannot be found within the very systems that are brutalizing and murdering our people. As Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Two Spirit, Trans, and Gender Non Conforming People of color, we are very aware that these systems were built to tear us down. We are committed to and continue to heal, lift up, and organize against all forms of hate, communal and police violence, and genocide. We know that we have the power, the resilience, and the strength to transform this culture of violence which regards our communities expendable, invisible, and dangerous.

In the words of Audre Lorde, ‘We were never meant to survive.’ Our survival, our continued resilience, our continued efforts for social justice are direct threats and challenges to systemic oppressions. We must, at all costs, do whatever we can to lift up and protect one another in our interconnected struggles for liberation.

And of course, the calls to action in the wake of Michael Brown’s death have been part of almost all the analysis. Here’s Jessica Pierce, national co-chair of the BYP100:

As a Black feminist who works for and with a Black youth organization that operates with a focus on radical inclusivity and from a Black queer feminist lens we look to Ferguson, Missouri [,] and we see more than just the current turmoil and terror on the streets there, we see more than just the murder of Mike Brown. We see the lives of those women who become nameless and forgotten in these moments like Rekia Boyd, Yvette Smith, Tarika Wilson and many others.

We also realize that is moment for reflection but also for action. Reflection to ensure that we develop a unified community that is informed and understands that violence is a system. It is a system that has been built into the very foundation of this country. It is a system that must be dismantled because oppression stems from patriarchal systems. We need action so that we can ensure that we get justice for more than Mike Brown. We need justice for all the victims of police violence, sexual violence, and domestic violence. We need justice for people like Mike Brown and people like Marissa Alexander. We need a justice that is not punitive in nature, but is transformative and lasting.

We need justice that recognizes that Black lives actually matter. Not just Black heterosexual male lives but all Black lives.

Read a full statement from the BYP100 here.

I’ll end this with Melissa Harris-Perry, who often provides important historical context for these moments: