Simranjit Singh doesn’t know how many countries he’s traveled through to get to the United States. The 22-year-old hails from the northwest Indian state of Punjab. As a Sikh, he lived in fear for his life because of his religious and political beliefs. Now Singh is part of a group of immigrant detainees awaiting release from a detention center Texas known as the El Paso 37–although the number of people from India hoping for parole appears to be higher.

Attaining asylum in the United States first hinges on the ability to establish a credible fear of persecution or torture with immigration authorities. New policies established in 2010 indicate that potential asylees already in detention who demonstrate that plausible fear are automatically considered for parole from detention until a judge hears their case. But that policy doesn’t always translate into practice. Singh surrendered to immigration officials at a port of entry in May 2013. He was granted an interview and established credible fear a few days later but languishes at the El Paso Processing Center nearly one year later.

Singh’s asylum claim isn’t unusual for Sikhs from India. The height of violence there struck in 1984, when thousands of Sikhs were killed by paramilitary action and rioting. Thirty years later, the likelihood of violence remains. In 2006, the United States allowed India to extradite Kulvir Singh Barapind on serious charges, although Barapind held that Indian officials previously tortured him. Six years later, in 2012, Barapind reported that he was once again severely beaten and tortured with electrocution.

After having survived several beatings from mobs as well as police in Punjab, Simranjit Singh moved to Delhi, in hopes that the persecution would stop. But he was attacked once more. Singh then obtained a passport and travelled to the South American country of Suriname in January 2014. Throughout the next four months, Singh went through no fewer than eight countries before arriving in Mexico–sometimes by walking, sometimes by car, truck or bus. "I don’t know which countries I went to from Suriname," says Singh. After crossing Mexico he surrendered to immigration officials at the port of entry in El Paso, Texas.

Singh was placed in detention and thought he would be released after passing his credible fear interview. His uncle, Jagroop Singh, lives in Seattle, along with Simranjit’s other family members, including grandparents. Jagroop Singh visited the detention center in El Paso, and has sworn to immigration officials that he would take full responsibly for his nephew once he’s released on parole.

"I can provide him everything," says Jagroop Singh, who is a U.S. citizen who received asylum himself after arriving on a visa in 1999. "I have no idea why he has not been released," he adds, with a deep frustration in his voice.

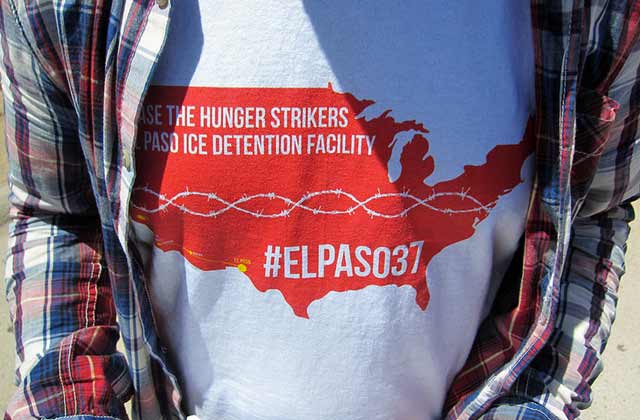

Simranjit Singh was one of 32 men whose names appeared on a document in December 2013, who had passed their credible fear interviews but nonetheless remain in custody at the El Paso Processing Center, which is managed by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. In April, Singh and several others began a hunger strike and were subsequently placed in solitary confinement. Several groups began to take up the cause of the El Paso detainees, including the Jakara Movement, a social justice organization for Sikh youth.

On April 25, Jakara Movement members traveled to El Paso to visit the detention center. They found that at least one of the 45 or so detainees awaiting parole after establishing credible fear has been there for up to 17 months. Executive Director Deep Singh (no relation) says it makes no sense that so many detainees continue to be held in contradiction to government policy.

"They’re being indefinitely held, and their hunger strike came about as an idea to highlight their cases in whatever way possible and give some sort of voice to their frustration at this injustice," explains Deep Singh.

But it hasn’t only been family members and supporters who have visited El Paso. Simranjit Singh says that he was visited–and intimidated–by members of the Indian consulate who came in from Houston during his hunger strike. The revelation is troubling: If U.S. immigration authorities agree that there is a credible fear of violence on the part of the Indian government, it seems unusually cruel to allow the consulate to visit the detainees who fear for their lives.

Simranjit Singh says that the consulate didn’t treat the detainees favorably, and suggested they would be deported. "He came, he asked why [we] were on hunger strike," says Singh. "He was against us, and told us he would take us back to India," before trying to pressure the detainees into signing documents that would result in their deportation.

Citing privacy concerns, U.S. immigration officials will not comment on a particular case, and the Indian consulate has not responded to requests to clarify what occurred.

After a journey to preserve his own life that started in January 2013, across an ocean and about a dozen countries, Singh awaits his final hearing before an immigration judge next month. Yet by phone, he deflects the attention.

"I don’t want people to know about my case, because I’m not alone over here. There are 40 or 50 Indians here, and we all face the same problem," he says.