Placing black and Latino men at the center of race discussions in America is, of course, nothing new. But in recent years, as we discuss what seems to be a growing number of black and brown victims of police and vigilante violence, the conversation about race and masculinity has taken on a more urgent tone.

Two new art exhibits in New York City by openly gay men of color grapple with some of the sentiments that animate the discussions around black and Latino masculinity.

The first, and more celebrated, is Kehinde Wiley’s exhibit "A New Republic" at the Brooklyn Museum. Wiley’s work–often reproductions of famous 17th- and 18th-century European paintings that feature black people rather than white aristocrats–makes a simple-but-powerful statement: "We exist."

"Painting is about the world we live in," Wiley tells Colorlines. "Black people live in the world. My choice is to include them. This is my way of saying ‘yes’ to us."

At just 38, Wiley is among America’s most celebrated artists. Since roughly 2001 he’s painted enormous portraits of black men who mimic the poses of so-called Old Masters. The artist began this work while he was doing a residency at the Studio Museum of Harlem. He was walking down 125th Street and came across a crumbled piece of paper on the sidewalk. That paper turned out to be an NYPD mugshot of a young black man, head tilted slightly to the right, wearing a blank and impatient expression. That image forced Wiley, who’d been studying European portraiture since his childhood, to reconsider what the form says about power.

"[That piece of paper] made me [think] about portraiture in a radically different way. I began thinking about this mugshot as portraiture in a very perverse sense, a type of marking, a recording on one’s place in the world in time," he told Helen Stoilas in a 2008 edition of The Art Newspaper. "I began to start thinking about a lot of the portraiture that I had enjoyed from the 18th century and noticed the difference between the two: how one is positioned in a way that is totally outside their control, shut down and relegated to those in power, whereas those in the other were positioning themselves in states [of grace] and self-possession."

That line of inquiry led Wiley to the create pieces such as "Mugshot Study" (2006), a portrait of the man in the mugshot that obscure the NYPD processing information. The painting gives the subject an angelic look and also challenges the viewer’s implicit bias.

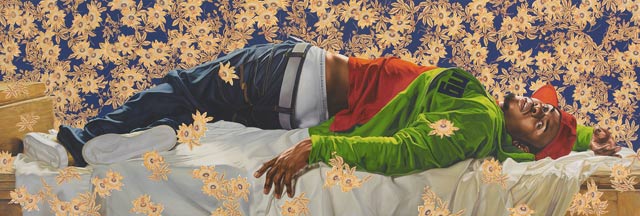

More portraits followed. There was his 2008 reproduction of the 19th century French painter Auguste Clésinger’s "Femme piquée par un serpent" (pictured above) in which a young black man in a red fitted cap, green hoodie and blue jeans is laying down sensually with his face tipped toward the viewer and his underwear exposed. After Michael Jackson’s death in 2009, Wiley made him the subject of "Equestrian Portrait of King Phillip II (Michael Jackson)", a riff on a portrait of the 16th-century Spanish monarch.

Most of Wiley’s subjects have been far less famous than the King of Pop. They are instead chosen for his participatory art-making process. For example, Wiley has recruited black men in their late teens and early 20s on the streets of Brooklyn, invited them to his workspaces, and had them choose an 18th-century portrait to mimic. He would photograph and eventually paint these men in poses that play up their vulnerability. "My work is political and it is religious, but it’s also decidedly homoerotic," Wiley explains. "When I’m approaching these guys, there’s a presupposed engagement. I don’t ask people what their sexualities are, but there’s a sense in which male beauty is being negotiated in each of these works."

While occasionally ridiculed as "too bright" or "kitsch," Wiley’s work has become so widely admired that it’s even featured on Fox’s new hit show "Empire."

What sets the Brooklyn Museum show apart from others is that it’s a through-and-through survey of his work, which exists across multiple forms. Along with some of his more well-known portraits of black men, it also features his only known video installation, "Smile," stained glass paintings, sculptures and several works from the collections he did in China, Israel, and India. Several new works are also drawn from his time in Haiti and Jamaica, and they prominently feature black women.

The second artist at issue has work tucked within a larger exhibition at SoHo’s Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art. The show, "Irreverent: A Celebration of Censorship," features several paintings from Alex Donis’ doomed 2001 exhibition "WAR." Provocative and controversial, these pieces feature hilarious and intimate scenes of Watts gang members in various dance poses with LAPD officers. Under the threat of protests and community violence, The Watts Towers Art Center canceled "WAR" two weeks before its debut.

A little more than a decade removed from the 1992 Los Angeles uprising, Donis’ "WAR" paintings took tensions that had long roiled Los Angeles’ black and Latino communities and mocked them with homoerotic disregard.

"Spider and Officer Johnson" (2001) by Alex Donis

"Scoob Dog and Officer Morales" (2001) by Alex Donis

"Scoob Dog and Officer Morales" (2001) by Alex Donis

The question piercing through Donis’ work, as articulated by Jaime Villaneda in an essay from the original "WAR" catalogue, is the same one that Rodney King infamously asked in the midst of the ’92 uprising sparked by his videotaped police beating: "Can we all just get along?"

The answer, especially recently, as communities have spoken out against racist police and vigilante violence in places like Ferguson, Staten Island and Denver is a resounding "no."

In the 1951 essay "Many Thousands Gone," James Baldwin wrote, "It is only in his music, which Americans are able to admire because a protective sentimentality limits their understanding of it, that the Negro in America has been able to tell his story."

Wiley and Donis have been using their visual art to tell stories of black and brown manhood in America, stories of men who’ve been erased, hunted and hated.

Now, more than ever, America is looking.

The Brooklyn Museum of Art began showing "A New Republic" on February 20; it will remain until May 24.

The Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art opened "Irreverent: A Celebration of Censorship" on February 13. It will be there until May 3.