The smell of sage rose over the thousands of marchers who came to Washington, D.C. March 10 for the Native Nations Rise March. The fragrance burned throughout the day, leaving ash and smoke in its wake. Marchers were there to demand President Donald Trump re-evaluate his decision to approve the completion of the Dakota Access Pipeline and acknowledge Native sovereignty. They began outside the Army Corps of Engineers Headquarters on G Street and ended in front of the White House.

But marchers had to make one stop first: Trump International Hotel. There, water protectors engaged in a street performance inspired by the Buffalo Dance of the Oceti Sakowin people. They erected a 14-foot tall tipi, one of the smaller ones on hand. Nine men carried the three sets of poles to the front of the building on Pennsylvania Avenue. They quickly got the poles up, covered it with tarp and began a ceremony.

{{image:2}}

Indigenous women held symbolic staffs, while the youth carried cutouts of various animals. Then, the men held a cardboard cutout of Trump. It was up to the women to bring it down with their staffs.

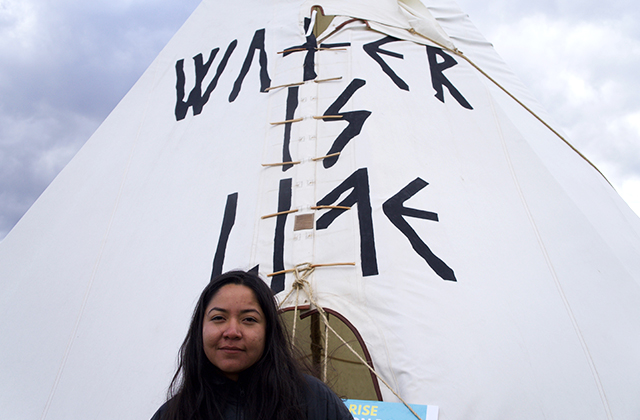

None of these actions happened on their own. They required organizers, people behind the scenes. Meet Eva Cardenas. She’s a program coordinator with The Ruckus Society, an organization that provides support for nonviolent direct actions. Cardenas is a 29-year-old Mexican Indigenous woman, of Zapoteca and Mazahua background, who spent two weeks in Standing Rock, North Dakota, to give trainings on behalf of the Ruckus’ Indigenous Peoples Power Project in the middle of winter. She’s continued to support the fight against the 1,172-mile long “black snake,” as Native opponents refer to the pipeline, back in Atlanta, Georgia, where she lives, and also in the District of Columbia for the march.

“Doing this work has allowed me to ground myself a little bit more as to who I am as an indigenous person,” says Cardenas.

In D.C., she was the main driving force behind erecting a tipi outside the Trump hotel, an action, as she put it, that won’t solve the issues facing Native people, but will bring awareness to them—in particular, Standing Rock. "We’re bringing this notion of this is an issue but not just for indigenous people," Cardenas says. "For all of us."

Cardenas stepped out of a car and in front of the Army Corps headquarters in D.C. Her small frame—no taller than five feet—made her easy to lose in the crowd of marchers that organizers say swelled to 5,000. As soon as she arrived, she was focused on securing the area for the tipi erection outside the Trump hotel, which march organizers asked her to coordinate.

Along with other lead organizers, Cardenas briefed a core group of volunteer fire marshals. She needed them to make sure that those people responsible for putting the tipi together—including those who were carrying the poles—were to the front, left side of the march, ready to jump into action once they turned onto Pennsylvania Avenue, where the hotel is located.

Cardenas might be small, but appears to carry the spirit of her ancestors, using her voice and body to command the crowd to where she needed them and ensuring the action went smoothly. The tipi went up; indigenous women conducted their ceremony. A youth sang, and a cardboard Trump was hit with metaphoric arrows. No police intervened, and no poles knocked out any teeth.

Once the action was over, Cardenas relaxed. The Native Nations Rise March was not her first rodeo. She’s provided support for, she estimates, five marches of similar size in the past.

Her first Indigenous-based march was just last year in September 2016. She helped organize a Water Is Life Solidarity Action in Atlanta with migrants rights activists. The Native Nations Rise is the only other indigenous-focused march for which she provided support. Most of her previous experience revolved around migrant rights.

Though her name has not yet rose to the ranks of, say, the Indigenous Environmental Network’s organizers Dallas Goldtooth or Kandi Mossett, she’s someone these organizers respect. Goldtooth shouted her out in a Facebook post after the march. Mossett speaks only positively of Cardenas: "She’s so down to earth and real about the work that we do, and it’s basically for the betterment of all people."

Cardenas’ exploration of Indigenous organizing—and how it connects to her personal roots—may only be starting, but it’s an area that runs deep for her.

{{image:3}}

Cardenas was born in Mexico in 1987. Her father came to the U.S. at just 17 to support his mother and family; her mom followed him about eight years later. She and her younger wo sisters were raised by her abuelita.

Cardenas migrated to Georgia at the age of 10 to join her parents. She helped them translate documents and constantly heard her mother dictate the importance of learning English to avoid being taken advantage of by others. She also served as an interpretor for family friends and neighbors dealing with issues like wage theft. She didn’t realize it then, but all this was preparing her to take on migrant rights.

By 21, Cardenas was working closely with Georgia-based organizers. First, with the Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights (GLAHR) from 2009 to 2010. Then, as a paralegal for the Southern Poverty Law Center in 2011. She eventually took her work to the national level with The Ruckus Society.

"I do this work in honor of our ancestors and the future of the seven generations to come," she says. "Based on everything that I’ve experienced in my life, it’s more a question of, ‘Why wouldn’t I be doing this work?’ It just makes sense. I have a responsibility to my people because of the privelege I have to do this work as a paid organizer."

At The Ruckus Society, she leads support efforts for different actions. Last year, she helped coordinate Ruckus’ #WallOffTrump action with Mijente during the Republican National Convention in Ohio. "We wanted to send a clear message against the rhetoric of hate that Trump utilized to gain popularity and our commitment as working people to our communities and our struggles," Cardenas explained in an email to Colorlines.

She also helped execute a Shut It Down action in Atlanta against Immigrations Customs Enforcement (ICE) in 2013. Organizers from immigrant rights groups like GLAHR and Southerners on New Ground locked down the gates of an ICE office as part of the larger #Not1More Deportation campaign. Law enforcement arrested nine people.

Cardenas remembers one training with the Indigenous Peoples Power Project in 2015 particularly well and for an unexpected reason. She was still a student-trainer then. Every Indigenous at the meeting introduced themselves in their Native tongue and with an understanding from where they come. When she introduced herself, all Cardenas shared was her name and that she was from Mexico. “I felt like crying because … that’s as far as I go,” she says.

While Cardenas is indigenous, her family wasn’t very connected to their Indigenous roots. It was was more of a romanticized notion, she says, something they never really talked about. Except her abuelito.

He told her stories of his growing up in Oaxaca, Mexico, a Zapotecan part of Mexico that colonizers never truly conquered, she says. He explained that her great grandfather fought alongside Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata during the Mexican Revolution in the early 1900s.

She headed to Oaxaca in July 2013 to see this history firsthand. “I found it’s very helpful to go and talk to the actual people there because their ancestral knowledge that they hold within is very powerful,” Cardenas says. She prefers that to reading academia and books on the history because, as she says, “it’s very Whitewashed.”

Cardenas spent two months in Oaxaca. She was there during la Guelaguetza, a summertime festival in Oaxaca that is embedded in Zapoteca roots where community members bring food to share with everyone for free. Cardenas described it as a 10-day long potluck, but with more dancing and ceremony. Cardenas felt inspired by the selflessnes she witnessed and it reminded her that despite nationality, Latin American communities are indígenas first. "We have this responsibility to one another," she says.

Then, in 2014, her grandfather passed away from a heart attack. “That personal connection was gone,” says Cardenas. Five months after his death, she returned to Oaxaca to meet her family and spent two weeks exploring more of her history.

Though Cardenas acknowledges that she has a long way to go in truly understanding from where she comes, she knows enough to bring this knowledge into indigenous and migrant spaces to help move the work forward, as she’s done in Atlanta, Standing Rock and Washington, D.C. She’s especially interested in bringing more collaboration between migrant rights folks and indigenous peoples who might not always see how their struggles intersect.

La Guelaguetza showed Cardenas what community looks like in her indigenous culture. That trip was the first time she felt that sense since her days in Mexico; she didn’t feel that again until she arrived to Standing Rock in November 2016.

A ferocious blizzard hit the #NoDAPL camps near the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe reservation in November. Cardenas, a southerner born in Mexico, was not a fan of such weather. “I’m not about this life,” she laughed, as we sat in a coffee shop near the rally that followed the march. “I’m from down South. I can’t do that.”

Cardenas couldn’t fathom the thought of her Indigenous ancestors who had to once endure such weather without the technology available today. But what really left an impression on the Xicana was the sense of community she felt at the Oceti Sakowin Camp, whose numbers swelled well into the thousands at the height of the encampment movement during the summer. She saw women running the kitchen and core organizing, serving as anchors to the many people gathered. “That’s something I hadn’t experienced since I was in Mexico with my abuelita and auntie,” she says. “I remember feeling at home even though I had never been to North Dakota before.”

Now, Cardenas is taking this spirit with her as she and The Ruckus Society prepare for other Indigenous fossil fuel battles across the country like the Seminole Tribe’s fight against the Sabal Trail Pipeline in Florida, which will also run through Cardenas’ home base of Georgia, or the Apache resistance against mining Oak Flat for copper in Arizona.

{{image:4}}

More importantly, she and her team are trying to figure out how these movements can work with others like the Movement for Black Lives or #Not1More Deportation—beyond one group just attending another’s march or rally. The reasons why Cardenas does this work are many, but the linkages to her past and future definitely loom heavy over her.

“I do it for my daughter,” Cardenas says, speaking of her 11-year-old. “I also do it because of my grandpa because I want to keep him alive in that way.” He was an indigenous man and an immigrant, the cornerstone of Cardenas’ journey to finding her indigenous roots. She keeps him alive by working to bring these struggles together—unidos.