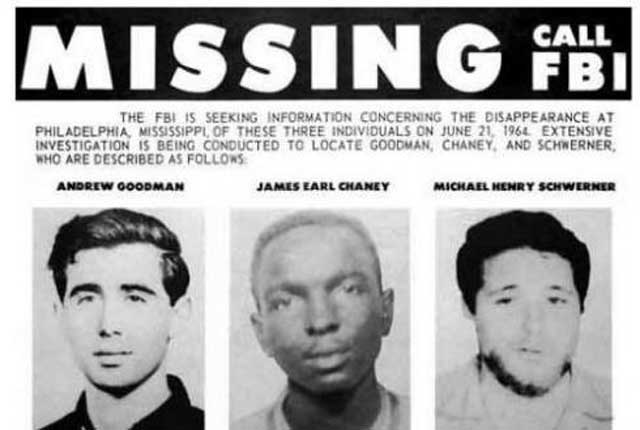

In the summer of 1964–Freedom Summer–more than 1,000 Northern, mainly white students traveled for the first time into the Deep South. Besides registering blacks in Mississippi to vote, the strategy behind Freedom Summer was to use young white bodies to draw national attention to the legal campaign of terror visited on Southern blacks. Colorlines continues its Freedom Summer 50th anniversary series with Heather Booth, 68. As she headed down into Mississippi in late June, news broke that three volunteers had gone missing. They were James Chaney, 21, from Meridian, Miss. and Andrew Goodman, 20, and Michael Schwerner, 24, from New York. Booth was 18 at the time.

My family was very close before I went down. I don’t actually remember a previous family conflict. But then we were told in Oxford, Ohio, that the three men were missing. When I spoke to my folks the night before I was leaving to go down to Ruleville, Miss., I recall my father raising his voice. He was yelling into the phone. My mom was so overcome she couldn’t talk. She was just crying. Dad didn’t say I couldn’t go. But he kept yelling, "Do you know what a human life is worth?" Over and over again, he just kept asking me that.

Before that summer, I’d been struggling to find a way to live my values, my parents’ values. I went to high school on the North Shore of Long Island where I was a cheerleader. They didn’t allow a few blacks kids to be on the team so I quit. I joined a sorority and left soon after realizing they only took kids with certain "conventional" looks. I joined CORE in 1960 to support the demonstrations against Woolworth’s in the South. By the time I got to college in 1963, within two weeks I was extremely engaged in civil rights. When I heard about Freedom Summer I immediately knew it was something I wanted to do. If by going down there we could bring the attention of our families and the media, they might decide to care to stop that system of abuse and terror.

I was frightened all the time. I was insecure. I think lots of young women especially are. I was afraid that I didn’t know enough, that I might harm someone else with my actions. I was also frightened for my life. But I realized that poor black people in Mississippi lived with that kind of terror every day. I only learned later that while looking for the three missing young men, they found the bodies of eight other black men. Their hands were found. Their feet had been chopped off. They’d been thrown into the Mississippi River and those murders had never even been reported. That’s the level of terror that black people lived with. [Pause.] I want to tell you what happened to the Hawkins family.

That summer, after Ruleville, I went to Shaw next and lived with Andrew and Mary Lou Hawkins and their children. Their generosity was breathtaking. We had three or four volunteers in their double bed and they slept somewhere else, probably on the couch in the living room. The black community in Shaw had no indoor toilet plumbing, no sewers, no streets or sidewalks. Civic improvements came later though because after that summer the Hawkins’ signed on to a lawsuit challenging that a city can’t improve the white part of town unless they make comparable improvements in the black part. They won but at great cost. Their home was firebombed twice. The second time, a son and two grandchildren were killed. Soon after the decision, a cop came to the house, got into an argument with Mrs. Hawkins and killed her in 1972. Four murders in one family because people stood up; that should have been national news. I didn’t learn about any of this till the 1980s.

I wrote a lot of letters home to my brothers that summer but I’m not sure how often I wrote* to my parents. That phone call created a rift–but while I was down in Mississippi my folks were doing their part. Dad, a physician, helped support the Medical Committee for Human Rights. And Mom lobbied politicians to provide greater federal protection and to investigate what was happening. She said she’d gone to visit our congressman and he basically said, "Look, they brought this trouble on themselves. If they feel they need protection why did they go?"

I didn’t go down there that summer to have an interesting experience. We were doing this to generate national attention and stop that kind of terror where a sheriff, for example, would release a young man to the Klan. And to a large extent that has happened. But then Trayvon Martin happens or that young man, Jordan Davis, is killed for playing loud music. People in a fast food restaurant can sit together at a lunch counter now but fast food workers can’t afford to support their families. We’ve made enormous progress and it shouldn’t be minimized. But we still have a long way to go.

Six weeks after Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner went missing, police, on a tip, found their bodies on August 4, 1964. They were buried deep in an earthen well in Philadelphia, Miss.

* Post had been updated.