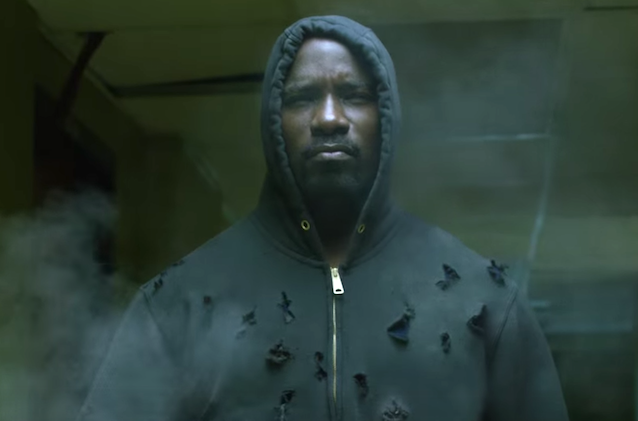

Thanks to an epic trailer and music from some of hip-hop’s finest, it’s no surprise that Marvel fans eagerly await the September 30 debut of “Luke Cage” on Netflix.

Cage—a Black man in Harlem with bulletproof skin and superhuman strength—was first introduced in a 1972 Blaxploitation-style comic book, but the character has resurfaced in our pop culture consciousness due to his appearances on another Netfilx series, “Jessica Jones.” Actor Mike Colter plays Cage as deceptively gruff, ambivalent about his powers, damaged by the murder of his wife and fiercely protective of his sometime-lover Jessica Jones.

While their complicated affair is titillating, it’s Cage’s origin story that situates the show in an interesting conversation for the #BlackLivesMatter era.

In his 1972 debut in “Luke Cage: Hero for Hire,” Cage is imprisoned for a drug crime he didn’t commit. He agrees to participate in a cell regeneration experiment that he hopes will count toward “good behavior” time. But in retaliation for Cage’s refusal to serve as a prison informant, a vindictive police captain sabotages the procedure. Cage is tortured during the experiment but develops a mutation that “increases his muscle mass, makes his skin tough as steel, and enables him to regenerate and heal at an accelerated rate,” writes Loyola Marymount University professor Adilifu Nama in “Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes.” With his newfound powers, Cage busts out of jail and becomes a vigilante for profit.

The meaning of the Cage story in the early ’70s isn’t the same as it is in 2016. What does it mean today to watch a bulletproof Black man on Netflix then flip to graphic videos of police fatally shooting, beating and choking African-Americans? How do we begin to think about a impenetrable Black hero in a society with a long history of depicting Black people with superhuman strength?

These are not abstract questions. In a recent study on how medical students and residents view Black physicality, University of Virginia researchers found that a substantial number of White participants believed that Black people have different biological attributes, such as thicker skin and blood that coagulates more quickly.

“The one consequence that our data can speak to is racial bias in pain perception,” lead researcher Kelly Hoffman said in an NPR interview. “We know from a lot of work that Blacks are systematically undertreated for pain relative to Whites. And so this super-humanization might suggest that one reason that they’re undertreated for pain is because people perceive them as having more strength and being less susceptible to pain.”

Hoffman’s results harken back to the dark eras of American scientific history—barbaric experiments that Dr. James Marion Sims conducted on enslaved Black women, phrenology, the study of eugenics, and the Tuskegee Experiment.

More recently the myth of Black super-humanity emerged in police officer Darren Wilson’s grand jury testimony about his fatal shooting of Michael Brown. His description of Brown as a grunting “demon” who “bulked up” and ran through multiple bullets sounds like it’s straight out of a comic. Luke Cage may be imaginary, but he still exists in a country where he is 2.5 times more likely to be shot and killed in a police encounter.

And of course this perception has made its way into pop—and comics—culture. We see it in the “Luke Cage” Netflix trailer when the he marches through volleys of bullets. In Issue 5 of “Power Man and Iron Fist, the current Cage comic book series, the heroes fights Manslaughter Marsdale, a bulky Black villain whose superpower is that he can’t feel pain.

But while we can problematize Cage within a modern context, he still remains a hero. In “Super Black,” Nama describes him as the most “inherently political and socially profound Black superhero to ever emerge.”

“Given Cage’s origin narrative as a black man who was wrongly convicted of a crime he didn’t commit, he clearly symbolizes the triumphant transformation of a black underclass convict to a politicized black antihero…Most importantly, the character’s literal mutation from Lucas to Luke Cage is bound to issues of unjust black incarceration, black political disenfranchisement, and institutional racism in America.”

“Luke Cage” show-runner Cheo Hodari Coker sees the show as an antidote to the constant state violence against Black people. “When I think about what’s going on in the world right now, the world is ready for a bulletproof Black man,” the producer said in July at Comic-Con.

Representation also matters. While racial diversity in comics is growing, there remains a dearth of non-White lead characters. In its 2014 diversity survey, The Open Book blog found that of the 100 top domestic grossing sci-fi and fantasy films that year, only eight casted a lead character of color. None of them were women, and six are played by Will Smith.

“Luke Cage” will be one of the first Netflix shows to feature a cast that is predominantly people of color including Rosario Dawson, Alfre Woodard, Mahershala Ali, and Simone Missick as the kickass crime-fighter Misty Knight.

“This representation is extremely important because it shows not only the success of Black superheroes, but of Black shows in general," says Constance Elly, the TV editor of Black Girl Nerds. "With Misty Knight in the equation, many Black women are going to look to her to be her own hero much of the time."

Like other art centered on marginalized people, the Netflix adaptation of “Luke Cage” is bound to be both politically challenging and powerful. This series could be a seminal moment in which pop culture reflects on the issues of the day with both color and clarity.

Joshua Adams is a writer and arts and culture journalist from the South Side of Chicago. He holds a B.A. in African American Studies from the University of Virginia and a Journalism M.A. from the University of Southern California. His writings often explain current and historical cultural phenomenon through personal allegory. Currently, he is working on a young adult novel.