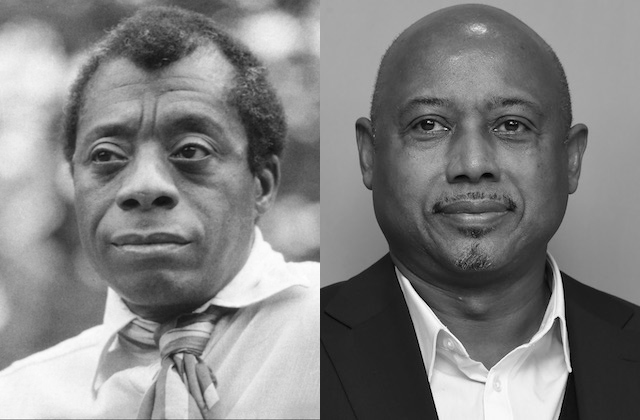

Raoul Peck’s "I Am Not Your Negro" does not simply tell James Baldwin‘s story or discuss his legacy. Instead, the documentary inhabits Baldwin’s work, using the author’s original work to guide audiences through the themes that link the Civil Rights Movement and contemporary racial justice struggles.

Samuel L. Jackson‘s recitation of Baldwin’s unfinished "Remember This House" manuscript grounds the film in Baldwin’s prescient cultural commentary. Scenes from "Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?" and other old Hollywood films feature alongside footage and photos from the Watts riots, Ferguson uprising and assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Those scenes, framed by Baldwin’s words, show audiences the many faces of structural racism that Baldwin understood as connected when he wrote it back in the ’80s.

At a virtual roundtable with the Haitian filmmaker on Friday (January 13), Peck told press that Baldwin helped him understand the ways structural racism affected his own career and existence as a Black man. Before "I Am Not Your Negro" opens in theaters on February 3, we offer three quotes from Peck that show how Baldwin’s legacy still resonates in today’s racial justice battles.

On media and entertainment’s brainwashing:

When I started making films, I already had Baldwin in my mind. I knew what you can do with images and what they can do to you. I knew about propaganda and brainwashing. By the time I became a filmmaker, I was using Baldwin left and right. "Lumumba" was me, for the first time as a Black filmmaker, telling a story from my point of view in an industry that didn’t care. I had to fight to get the proper money, write a story they couldn’t refuse, etc. You can’t just make a film about someone killed by the CIA. So ["I Am Not Your Negro"] is the result of my own anger about the ignorance that exists today, how we ignore how important Baldwin is. Baldwin talks about television and the entertainment industry as something similar to the use of narcotics. And he wrote that 40 years ago, and we see how intense it is now. When you watch reality TV, it has nothing to do with reality.

On Sidney Poitier, "Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?" and the Black man in Hollywood:

When I was a young boy in Haiti, I would watch American films—Indians and cowboys, John Wayne, Doris Day. This shaped my imagination as it shaped those of many young boys and girls around the world. It gave them a piece of the American dream and taught them to see themselves as Hollywood showed them. It took a long time before you could see Harry Belafonte or Sidney Poitier on the screen, and even then, you discovered through Baldwin that there was a part of the story you weren’t told. I remember seeing "Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?" and feeling very proud because I could, at last, see a handsome Black man who speaks English well, is an intellectual and even gets the White girl. But at some point, I felt something was wrong. At the time, I couldn’t exactly put my finger on it. But Baldwin opened up and explained that they were using Sidney against us and making him something we, the majority, could never be. They set the bar very high and said, if you can’t be Sidney, stay in your ghetto. Baldwin helped us deconstruct the whole Hollywood creator of the Black image. Film and images are not innocent. There are many layers delivered in those beautiful law, adventure, sci-fi and horror stories. They bring things that prevent you from understanding who you really are.

On what Baldwin would think of the Black Lives Matter movement:

He would have supported it as he always did, whatever the movement was. Baldwin was one of the most generous individuals, even when some people in the movement criticized him for being gay or an Uncle Tom. He was a sort of mentor, raised money, visited people in prison, wrote letters for them. I’m pretty sure he would be in the streets with Black Lives Matter. We don’t have that kind of leader and intelligence anymore. Too much is at stake—people are afraid to lose their houses, mortgages, cars. Baldwin was never afraid of losing everything. That’s the price you pay, and if we’re not ready to pay that price today, we’re in deep trouble. There’s a total separation between young people and the streets and elders who should’ve been there with them. As Baldwin said, he had to be a witness and be there with the movement. We’re missing not only a voice like Baldwin’s, but also the sacrifice.

"I Am Not Your Negro" opens in theaters on February 3. Click here to see if the film will play near you.

(H/t The Guardian)