In 1921, Greenwood and the area known as Black Wall Street was a vibrant community of Black-owned businesses. Though there were poor members of the community, Black people in Tulsa had created a place of economic self-sufficiency, entrepreneurship and deep communal ties in the midst of entrenched segregation. The community had doctors, lawyers, beauticians, clothing shops, grocery stores, a high school, two newspapers and much more. This all changed in one day, on May 31, 1921.

Though historians don’t know exactly what started the bleak chain of events, one theory is that a Black man, Dick Rowland, stepped on the foot of Sarah Page, a young white elevator operator, at the Drexel Building. Another claim, is that Rowland touched her arm, and yet another report states that Page was assaulted by him. Beyond speculation, what we do know is when the elevator opened, Page screamed, Rowland ran away and a two-day riot was set to begin, leading to one of the worst incidents of racial violence in American history.

{{image:2}}

rn100 years ago, between May 31 and June 1, more than a thousand homes and businesses were burned to the ground. An estimate of between 100 and 300 Black Tulsans lost their lives. Thousands of armed white rioters attacked, looted and burned the businesses and houses of Black Tulsans. Some committed drive-by shootings, riding through Black residential neighborhoods and shooting any Black person they saw. Survivors later recounted planes flying overhead and dropping bombs filled with flammable material. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, the police mostly deputized and joined in on the destruction, while the National Guard was mobilized but “spent most of the night protecting a white neighborhood from a feared, but nonexistent, black counterattack.”

{{image:3}}

rnDuring the chaos, some Black Tulsans resisted while others fled. Many were put in makeshift internment camps or imprisoned. The only edifice to survive the eighteen hours of destruction was Vernon Chapel A.M.E. Church, a place where Black people hid to escape the violence. Though Rev. Dr. Robert Richard Allen Turner, the current pastor of Vernon Chapel, lauds the resilience of Greenwood, he points out the historical ramifications the massacre has had on the community.

rn“In this one or two block area, we still have about 26 Black-owned businesses in the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce,” Dr. Turner said. “But to go from like 600 hundred to less than 30, shows how far we have fallen. But there are still remnants left.”

At Vernon Chapel, the basement survived but the sanctuary and other buildings needed to be rebuilt. Reconstruction of the church started right after the massacre, and through community efforts and grants from local foundations in Tulsa, the main church building was fully rebuilt by 1928. The church has been in operation and growing in membership since then.

rn{{image:4}}

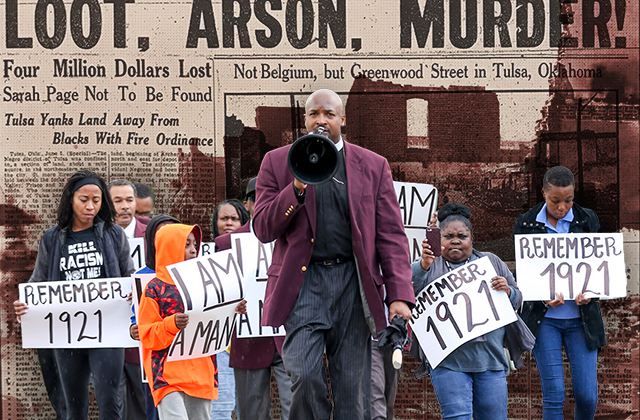

rnHistorians, activists, politicians and community members are working to both honor the victims of the massacre and keep the memory of this horrific tragedy alive. The city of Tulsa is hosting an array of events to honor the centennial of the massacre, such as art projects, vigils, officially recognizing historically significant locations in Greenwood, and a nationally-televised commemoration event with speakers and performers.

“There are several things we are doing to commemorate,” said Dr. Turner. “We are having a celebration of the stained glass windows created by the survivors, a prayer wall for racial healing, a revival, and there are other events going on around the community.”

Despite the commemorative events, all Tulsans are not interested in learning the importance of histories like this. In the state of Oklahoma, the GOP-controlled House voted to prohibit the teaching of critical race theory, a term conservatives have stripped of meaning and context to repurpose for their own needs.

But beside the preservation and retelling of this history, the community is still seeking the economic restoration they are owed. Descendants of the survivors have sued the city of Tulsa for reparations and for documents related to the massacre. Though honoring victims of the event and learning this troubling history is important, Dr. Turner believes that current and future efforts should be focused on reparations for those who perished.

rn{{image:5}}

rn“It’s justice that’s been delayed, it’s injustice that hasn’t been recognized and needs to be atoned for,” said Dr. Turner. “It’s important because it was hidden for so long and we need to make sure this incident of racial terror is known by everybody so it won’t happen again and so justice can be finally served.”

Joshua Adams is a Staff Writer for Colorlines. He’s a writer, journalist and educator from the south side of Chicago. You can follow him @JournoJoshua